Food Insecurity and Women in Conflict, By Haley Cook-Simmons and Sow Boubacar Guedé

Women experience higher food insecurity than men in every region around the world, with 150 million more food insecure women in the world than men. Among the major contributors are that women have fewer resources, opportunities, and access to information and decision-making as compared to men. Violent conflict further shifts options for women through decreased mobility, increased gender-based violence, and lower health and education outcomes, though it reduces working hours less for women and increases women’s employment in agriculture compared to men. Households led by women and girls, the elderly, disabled, minority populations, and other marginalized groups are especially vulnerable, as are displaced households that no longer have access to agricultural land and livestock.

Research Overview

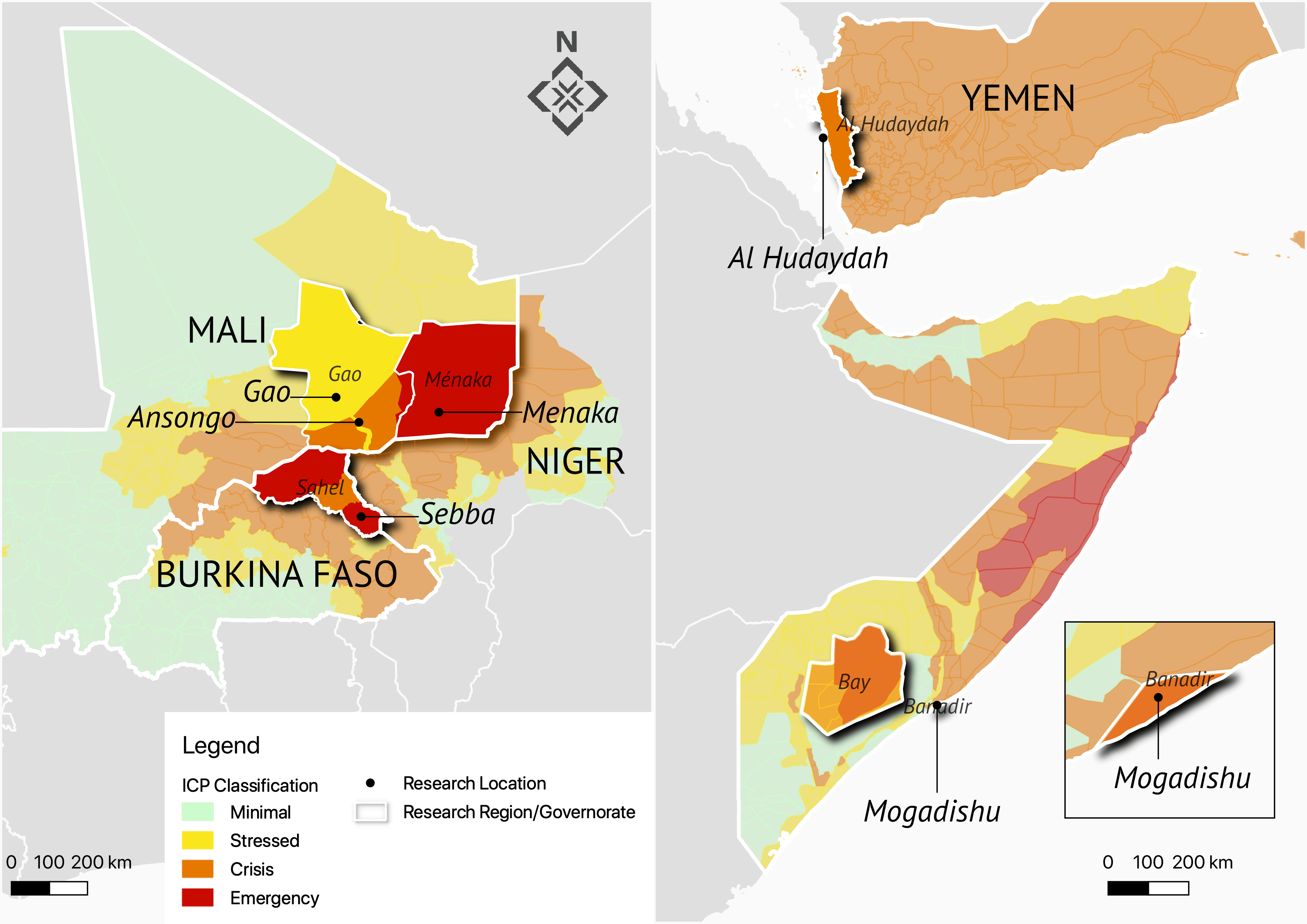

This article will illustrate how prevailing gender norms place female-headed households as more vulnerable to food insecurity following shocks from conflict, using key informant interviews from Mali, Burkina Faso, Somalia, and Yemen. Women and girls may come to be heads of household due to divorce, death or injury from illness or conflict, or split households where the male head stayed behind to guard land and livelihood assets while women and children fled to safer locations. Navanti originally collected 28 interviews with men and women in towns and rural areas in the Gao and Menaka regions of Mali and 4 interviews with men and women in Sebba, Yagha province, Burkina Faso to understand how conflict and displacement had affected communities. After this gender-sensitive research allowed for findings to uncover gender differences that displaced female-headed households from rural agropastoral settings were especially vulnerable to limited coping capacity, Navanti conducted additional interviews. These supplementary interviews were five interviews with female-headed households from rural areas (agricultural, agropastoral, or pastoral) in Al Hudaydah governorate, Yemen displaced following conflict to Al Hudaydah city, and five interviews with female-headed households displaced from rural areas of Lower Shabelle and Bay region to Mogadishu, Somalia.

Gender-sensitive research gathers the perspectives of both men and women and acknowledges that these different perspectives are shaped by gender roles within the community. Gender-disaggregated data allows for the development of gender-specific solutions. Unfortunately, traditional economic analysis focuses primarily on paid labor, which can ignore unpaid women’s contributions to household livelihoods that form a vital part of households’ food access. Even food security research can suffer from lack of a gender lens to understand gendered results; a 2020 review of over 100,000 research papers on ending hunger found that only 10% considered gender differences in their analysis despite unequal resiliency to climate change and food insecurity along gender lines. Navanti upholds the principles of gender-sensitive research, working to collect information on gender identity as a part of data collection, and include female data collectors for women to feel comfortable sharing information during interviews.

A 2020 review of over 100,000 research papers on ending hunger found that only 10% considered gender differences in their analysis

Background to Conflict

In northern Mali, non-state armed groups have a large presence while the formal state has little control. A 2012 uprising begun by various ethnic Tuareg armed groups culminated in the signing of the 2015 Algiers Accord peace agreement; unfortunately this Algiers agreement primarily engaged northern separatist groups while leaving out Islamic violent extremist groups and inadequately addressing ethnic rivalries. This led to a security vacuum filled by violent extremist groups, which despite the peace accord, have increased their violent operations in central Mali. Violence has since spilled over into the studied Gao and Menaka regions, as well as bordering regions of Niger and Burkina Faso, causing looting of livestock, civilian death, and displacement. The spillover of violence has even reached as far as the northern areas of Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Togo, and Ghana. Given this violence exacerbating the effects of pre-existing poverty and increasingly arid conditions from climate change, Gao and Menaka regions are the most food insecure in Mali. Civilians have been increasingly targeted: in Burkina Faso alone, extremist groups have killed more than 10,000 and caused displacement of over 1.9 million people. While the studied town of Sebba was once a refuge for those fleeing other areas, militants destroyed the only supply route into Sebba on June 25, 2022, causing many to flee again after experiencing food insecurity.

In Yemen, conflict between the internationally-recognized Republic of Yemen Government (currently based in the southern city of Aden, Yemen) and Ansar Allah (also known as the Houthis, in de-facto control of the state institutions of northern Yemen) has continued since the intervention of the Saudi-led coalition in 2015. Al Hudaydah governorate witnessed the displacement of over 445,000 people in 2018 as forces battled for control of Al Hudaydah city, and Al Hudaydah, Saleef, and Ras Issa ports. The UN-monitored Al Hudaydah ceasefire agreement currently places Houthi-controlled Al Hudaydah city as a safe location for families previously displaced from other parts of the governorate. After over eight years of wartime economic disruption in water-poor Yemen with climate change continuing to impact water availability, over 53% of Yemenis are experiencing high levels of acute food insecurity, especially displaced populations.

Meanwhile in Somalia, Al Shabaab is a violent extremist group fighting the Somali government for control of southern areas of Somalia for over 20 years. It is responsible for violence against civilians and civilian displacement, including the Bay and Lower Shabelle regions from where interviewees were displaced. Lower Shabelle experienced the highest number of Al Shabaab-related incidents in 2022. This conflict-related displacement comes amid a prolonged drought ongoing since 2015 that has prompted additional displacement to urban areas such as Mogadishu and need for humanitarian assistance as households are no longer able to grow crops and raise livestock with insufficient water. Agropastoral communities of Burhakaba in Bay region (origins of some of the interviewed households) and IDPs in Mogadishu (the community where interviewed households are now staying) are predicted to be at risk of famine April-June 2023, facing the worst food insecurity conditions in the country.

Gendered Contributions to Livelihoods

Women and men have different contributions to household livelihoods in the primarily rural areas interviewed households were originally from, where families depended primarily on growing crops or raising livestock. Livelihoods are the ways in which households secure their basic life necessities, including food, and are not restricted to paid labor. A household’s livelihoods for example could include not only paid work or sales, but also a household’s own food production – from crops they grow themselves, livestock they raise, or fish they catch. Rural women in developing countries comprise almost half on average of the agricultural workforce, but these are more likely to be women producing crops on family lands for household consumption with some sale of surplus crops, rather than paid labor opportunities or cash crop production and sale. Globally, when women do get paid for their agricultural labor, women earn 82 cents on the dollar compared to men for agricultural wage labor, while female-managed farms produce 24% less than male-managed farms. In Yemen, women comprise 60% of agricultural labor and over 90% of the labor in tending livestock, but due to unpaid household labor and gender discrimination, women earn 30% less than men. In Mali specifically, men and women have specialized roles in agricultural production where men primarily produce cash crops, and women mainly produce food crops. Aside from casual agricultural labor, women may find income earning opportunities, as in Somalia for example, in selling extra produce at the market above what the household consumed for its own needs; participate in petty trade such as selling tea, foods prepared in the home, firewood, or charcoal; or house-cleaning work. These acceptable casual labor and petty trade opportunities open to women such as those involving food production and cleaning resemble the unpaid household tasks performed primarily by women.

Acceptable casual labor and petty trade opportunities open to women such as those involving food production and cleaning resemble the unpaid household tasks performed primarily by women

“We were growing crops and keeping shoats [before our displacement]. The drought has killed all of our shoats and we couldn’t grow crops due to lack of rain. All able-bodied members of our family were working on the farms or with the shoats.”

-Female, Mogadishu, Somalia

A major reason rural women have lower direct involvement in food and income production than men is that they are more likely to engage in time-consuming, unpaid household survival tasks including child-rearing, gathering water and firewood, and preparing food – “the great engine of invisible labour that drives the rural economy” that in turn serves to allow men to specialize in earning income. In Mali, the responsibility of younger women for child-rearing and other household tasks leads to older women being more likely to work in agriculture or earn income compared to younger women. Aside from these essential survival tasks limiting women’s participation in agricultural labor, a 2021 review of 169 papers on gender in agricultural and pastoral livelihoods in West and East Africa revealed additional impediments to women farmers, including structural and cultural barriers of ownership and inheritance leading to lower land ownership compared to men, and the lower access to inputs including technology and information that would enable women to adopt climate-sensitive new crops, technologies, and farming practices. Lower rural female educational attainment compared to men contributes to women’s unequal information access.

Similar to crop production, rural men and women also generally have specialized tasks related to livestock rearing. In Mali and Somalia for example, women raise sheep and goats while men raise cattle and camels, which require requires a longer grazing distance from home that may prevent women from household tasks or take them farther than culturally acceptable away from the household. Somali women market sheep, goats, and dairy products in local markets, while men market livestock for export.

Gendered Access to Coping Strategies

The constraints surrounding women’s abilities to participate directly in producing food and income under a male-headed household also affect the livelihoods and livelihood coping strategies available to female-headed households, making them more vulnerable to shock without the benefit of male-dominated income and assets as women are more likely to face barriers compared to men. A livelihood coping strategy is a strategy employed by the household to get food or get money to buy food. While the primarily displaced households interviewed no longer had immediate access to their own farmland, it should be noted that should conditions improve for female headed-households to return home to their own communities they may still face land access or land tenure issues. In Mali these women may not be able to re-establish cultivation, as land access for widowed and divorced women was dependent on their husband’s land but was revoked, while in Yemen there is also no access to former marital land following divorce, and women may face difficulty or even gender-based violence in accessing inherited marital land or other property they own.

Women are more likely to reduce their own food consumption so others can eat, collect atypical wild foods, migrate, or have to sell remaining assets

As female-headed households seek to increase labor market participation by the woman head of household to get money to buy food, barriers include prior participation in household essential activities. In most of the households interviewed in Mali, these interviewed women are not enabled by extended family or circumstances to work outside the home, despite being widows, and must focus on child rearing and livelihood activities such as livestock rearing. Meanwhile, women who are able to work must compete with men for available opportunities; displaced households have an even smaller pool of labor opportunities. However, gender roles may provide some growing niche opportunities for women to find; in Yemen women are increasingly working in solar repair due to their ability to access customers’ homes in the daytime hours when only women are present at home.

“No, women are not allowed to work, it is men who take care of them and their needs. Besides, they are not educated to go to work in offices or in the administration, so they stay at home to take care of household chores.”

-Male, Menaka region, Mali

“Women are allowed to work, but for lack of economic means and support, they remain in the camp doing nothing.”

– Male, Menaka region, Mali

In the case of Yemen, Yemeni women originally from rural areas who were displaced to urban areas have greater opportunities for paid work compared to their rural home villages, but at the same time women in urban locations have less freedom of movement compared to women in rural areas. Then, when Yemeni women take their funds to market to buy food, they may encounter difficulty in some areas due to the norm that men traditionally purchase food from the market. These constraints on freedom of movement exist in other countries as well, giving women lower access to social capital as well through comparatively fewer opportunities to connect with neighbors, store owners, and others in the community that could have the ability to assist in a family’s time of need.

Gender roles may provide some growing niche opportunities for women to find; in Yemen women are increasingly working in solar repair due to their ability to access customers’ homes in the daytime hours when only women are present at home

Women also face greater difficulty than men in taking out loans or taking on debt. Men’s greater access to income to demonstrate ability to repay the loan is more attractive to lenders and gives them greater comparative ability to pay down past debt. Additionally, Yemen’s wartime collapse of available microfinance disproportionately affected women borrowers and entrepreneurs, decreasing from 80% pre-war to 40% women borrowers.

Women have less access to assets such as land, vehicles, and livestock to sell for money or use for a business venture. In the Mali interviews, there were some rare cases of women selling land, vehicles, equipment, or livestock of the deceased to pay debts incurred in the deceased’s lifetime, or expenses encountered after their death. However, following conflict-related displacement, households generally have lost access to their major assets through fleeing to another location, or having assets stolen in conflict as in the case of the Burkina Faso households no longer having livestock to sell because it was rustled. There was one interviewed displaced Burkina Faso household who still had savings to spend because they sold their land before leaving Sebba, but once those savings are depleted, they will have no way to replenish them and draw upon them for future needs. One notable exception to women-owned assets is gold, which some displaced Yemeni women are able to take with them.

“For food we had some support from social action and I had sold my undeveloped land in Sebba before leaving, so for now I am getting out of it a bit [of food].”

-Male, Dori, Burkina Faso

Given the gendered options for livelihoods available to women, certain livelihood coping strategies have emerged as more available and preferable to women. Interviewed women in Somalia, Mali, and Yemen added confirmation to the trend that women – including female heads of household – are increasing participation in labor and petty trade including family businesses and small home businesses, such as handicrafts and prepared foods.

Humanitarian aid from NGOs was highlighted by interviewed households in both Mali and Burkina Faso, however, no interviewed Yemeni households mentioned humanitarian food assistance or other NGO support. This may be due to the fact that displaced Yemeni women that are head of household can even lack access to life-saving humanitarian food assistance and other assistance programs due to difficulty getting the identity documents that can be a prerequisite to assistance eligibility and collection. Also, women have less access than men to transportation to access distribution sites, or travel without a male companion, both of which can be mitigated by on-site distribution in IDP camps, at least for displaced households living in camp settings.

Community groups such as women’s saving and loan associations or livestock marketing groups helped remove barriers for women to close the gender gap in access to livelihoods and more sustainable coping strategies

Social ties connect households with extended family who can share resources including money and food in times of need. In the interviews Navanti conducted in Mali, some related families previously habitually lived together and shared resources prior to experiencing conflict and the death of the male head of household, while other women changed their family living arrangements afterwards in search of additional support. One polygamous household with two widows split with each widow going with her own children to live with her respective parents. Another widow and her children were taken in by the deceased husband’s family. However, in another case the children were taken away from their mother by the paternal grandparents who are raising the children until they are old enough to take over the deceased’s business, leaving the children and mother negatively affected by the separation.

“Despite the fact that many have married, they still remain in the big family, and even men who marry girls in the family are usually settled there. So there is a traditional system of community management of property and income, where everyone contributes to the big family.”

-Male, Menaka region, Mali

Interviewed households in Mali, Yemen, and Burkina Faso also illustrated the importance of community members in social networks. Neighbors and those better-off in the community including local leaders and business owners will share food and money with households in times of need. Prior studies have also found that women’s associations in Mali (tontines, a kind of group annuity) are key to women’s social safety nets, with similar informal women’s saving associations (Al Jammaiyya or Haqba) present in Yemen as well, though opportunities have been shrinking as fewer Yemeni women can afford to participate in wartime.

“Since [my son’s] death, the family depends only on the social neighbors and our daughters who are married elsewhere and sometimes on humanitarian aid in case the village chief agrees to register us with humanitarian partners, especially with the WFP program.”

-Female, Ansongo, Gao region, Mali

“There is also an official from our village who lives in Dori who had paid us a bag of rice. In the meantime it is with that we feed.”

-Female, Dori, Burkina Faso

Just as there are differences in the mix of preferred coping strategies available to men and women, there are more extreme, less preferred options that women are more likely to be forced into instead of men. Women are more likely to reduce their own food consumption so others can eat, collect atypical wild foods, migrate, or have to sell remaining assets. In Yemen, selling assets to pay debt is viewed as a last resort, with gold being a specifically women-owned asset that might be sold after the death of a husband, divorce, or medical emergency. Once a household’s assets are depleted, which can happen more quickly with female-headed households due to possessing fewer assets, households may have no other choice than to turn to begging, with asking acquaintances or neighbors for food or money less stigmatized than street begging with strangers. Also, in Yemen begging by women and children is less stigmatized than begging by men.

“The reasons that pushed us to leave Sebba at first was hunger. We could not even go to the bush to look for leaves [to eat] because the terrorists were practically in the bush even to look for wood. If you come across them, they beat you if you are a woman but a man is simply killed!”

-Female, Dori, Burkina Faso

“[I did not want to] sell our remaining gold and household items.”

-Female, Al Hudaydah, Yemen

“Sometimes we are ashamed to ask the neighbors [for food], and sometimes we are forced to ask.”

-Female, Al Hudaydah, Yemen

“The main reason that I’m a street beggar is to get food for my family. I wouldn’t have done this if there were other alternative sources of income that we could get.”

-Female, Mogadishu, Somalia

Female heads of household who are mothers may also be forced to take their children under 16 out of school to work in casual labor, including girls, especially when adult women are constrained from working due to gender roles or household survival tasks, or household budgets are re-prioritized for life-saving food over school fees. Unfortunately, taking children out of school to work to be able to meet immediate needs limits their future pathways.

“The family lives on the help of neighbors and often young people go to the city to do daily work, since they are not in school and this is what keeps the family going.”

– Male, Menaka region, Mali

“My young son (12 years old) works as a shoe shiner. He wakes up every morning for this work in order to enable us to get food or money to buy food. He is at the age of studying at school like other children in our neighborhood, but in order for us to get food, he does the shoe shining work instead of studying.”

– Female, Mogadishu, Somalia

“I and my daughter whose age is 14 years work for our family. As we wake up every day, we go out to the neighborhood households and ask them if they need anyone to clean their clothes or their houses and that is one of the ways that we try to meet our needs.”

-Female, Mogadishu, Somalia

In the most extreme examples, women and girls may be forced into marriage or transactional sex to survive. In some areas of Mali, there is a tradition of levirate marriage, where a widow marries one of the deceased husband’s brothers. Levirate marriage keeps the widow’s bride price and children in the deceased husband’s family and may be the only livelihood opportunity available to a widow, but it is not always voluntary, as illustrated by one interview where a potential new wife did not want to participate. This remarriage is more likely to be as a less socially desirable second, third, or fourth wife. Although not mentioned by any of those interviewed, child marriage (especially of girls under 18 to men over 18) is a form of forced marriage on the rise in Yemen. Displaced female-headed households in Yemen are at risk of gender-based violence (including gender-based sexual violence) in seeking housing, such as situations of being unable to make a rent payment to a landlord. Additionally, one interviewed woman in Burkina Faso highlighted the phenomenon of widowed women being pushed into transactional sex in exchange for resources for themselves and their children in the absence of government support.

“Economically it’s fine, but socially it’s not. Lately it does not go well between the [widowed] wife and the family of the deceased since we have learned that there was one of the [deceased husband’s] brothers who wanted to marry the woman and she was not consenting, which explains the problem.”

-Male, Gao region, Mali

“We expect the authorities to resolve the crisis because we are touched in our dignity! [You can] spend your whole life waiting for money to be given. Some people come to take advantage of your vulnerability to make you indecent proposals (sleep with you) because we tell ourselves that you have no choice but to accept! Let the authorities do everything possible to resolve this situation.”

-Female, Dori, Burkina Faso

Solutions

In examining prior studies for successful interventions that would improve women’s overall access to livelihoods and thereby help give women alternatives to unsustainable short-term coping strategies, improving their food security, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) found over the past decade that the largest impacts on women’s empowerment and agency came from increasing women’s income, asset ownership and access to credit. One such systematic analysis/meta-analysis of 104 quantitative and qualitative studies from 2000-2021 involving 14 intervention types and 29 countries – specifically in fragile and conflict-affected contexts – identified women’s self-help groups as a key empowerment mechanism to increase income, assets, and access to credit. Community groups such as women’s saving and loan associations or livestock marketing groups helped remove barriers for women to close the gender gap in access to livelihoods and more sustainable coping strategies by providing women with increased assets through access to savings and credit; improved livelihoods through increased access to information, training, and social networks; and improved collective agency and positive change in discriminatory social norms and behavior.

At the same time, a World Food Program (WFP) on gender, markets, and women’s empowerment in the Sahel region has cautioned to avoid equating economic productivity with empowerment to avoid the issue of “overburden,” where paid work outside the home, such as for example a cash for work program, forms an additional time burden to women on top of the existing subsistence tasks and livelihood tasks in the home that they have to complete for their households. For example, although women’s savings and credit associations increase women’s income and financial assets, and can also be a positive pathway to women’s political participation for Malian and Burkinabe women experiencing food insecurity, women’s associations in Mali that are helping women market agricultural products ran into the issue of overburden where women still had tasks at home to complete that can interfere with participation. This led to older women being more likely to participate, whose older daughters or younger co-wives could instead take on household tasks. However, FAO found that formal, structured childcare is an intervention proven to address women’s household burden globally, which could be combined with economic empowerment programming.

Future Research

While the research in this article involves looking at case studies of differentiated outcomes by household headship and female-headed households in particular due to wanting to highlight the intersection of vulnerability between gender and displacement, FAO notes that existing gender-comparative data is largely limited to male versus female head of household. Gaps in gender data collection still exist for nationally representative country data in self-employment activities, time use, and access to assets. Additionally, a structured review of gender and agricultural and pastoral livelihoods in East and West Africa noted that data on intra-household decision-making (gender divisions on who makes decisions on livelihoods and resources and assets usage in the household) is also missing from existing gender analysis. Future research seeking to fill these gaps could therefore look at the way in which shocks such as conflict or displacement shape participation in livelihood activities and survival tasks, access to assets, and decision-making within the household.