Civilians in a street in Kismayo, Lower Juba region

On August 4, 2020, Commander of U.S. Special Operations Command Africa (SOCAF) Maj. Gen. Dagvin Anderson announced that the COVID-19 virus had directly affected al Shabaab (AS). Despite the group’s initial claims that the virus would only threaten non-Muslims, SOCAF confirmed that some AS leaders have both contracted and died from COVID. This allegation, to which AS has not responded, highlights the severity and lethality of the virus in AS-controlled areas. Given that the group has not been able to provide appropriate treatment for its leaders, the population living under its control is even less likely to receive adequate protection. Prior to the pandemic, poor health services were already a longstanding feature of life under AS, and consistently cited by residents in interviews as among the top community needs left unmet by the group. Aside from the short-term health consequences that are likely to develop from this lack of a counter-COVID strategy, AS’s inability to protect its population and combat the virus are likely to have severe long-term repercussions on its recruitment and expansion potential, given that the virus may spoil the group’s self-portrayal as a protector of the Somali people.

Since the COVID-19 virus began spreading across Somalia in March, the population has suffered severely, likely at a much higher rate than scarce testing shows, with cases surpassing 3,000 in July. Although the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) has attempted to educate civilians about preventative measures to combat COVID-19, cultural customs and a lack of economic sustenance obstruct efforts to practice social distancing. Furthermore, Somalia’s healthcare system, which ranks 194th out of 195 on the Global Health Security Index, is unprepared to treat patients once they are confirmed to be infected, with a lack of sufficient and accessible healthcare facilities and crucial equipment, such as ventilators. Additional factors, such as the number of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) living in crowded IDP camps, and the low number of testing sites available in Somalia, present reasonable evidence that the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in Somalia are likely much higher than government numbers show.

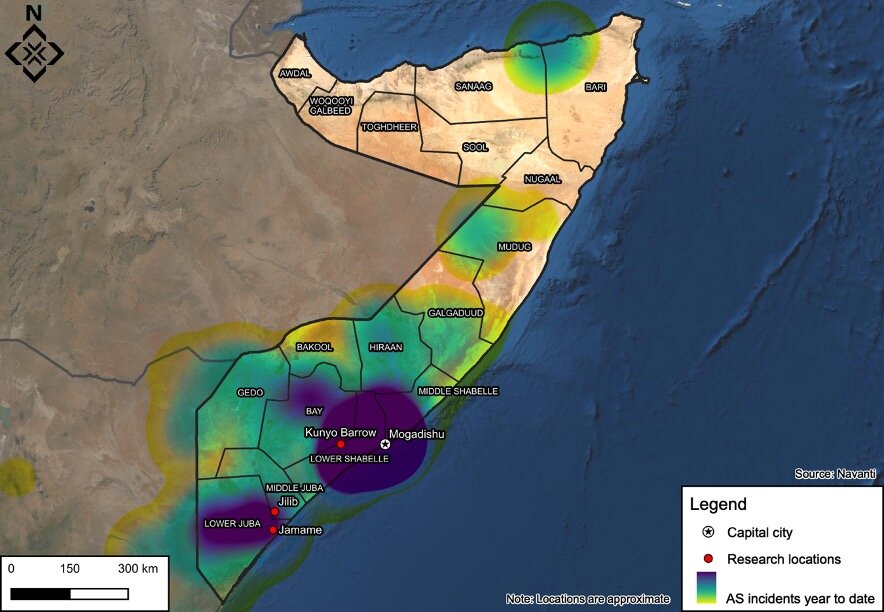

While the situation in Somalia and the FGS’s inability to adequately address the virus present a dire picture, Somalis living in areas under the control of the Al Qaeda-aligned AS face even more difficult conditions. AS is known to have used service provision as a way to build support from the communities it controls, and attempts to present itself as a better alternative to the FGS. However, data collected by Navanti local researchers from 15 respondents living in the AS-controlled towns of Kunyo Barrow, Lower Shabelle region, Jilib, Middle Juba region, and Jamame, Lower Juba region, highlight that AS appears to be unwilling or unable to provide the population with the necessary services to combat the spread of COVID-19. While this sample is not meant to be representative, the data collected from these respondents attempt to provide insight into highly inaccessible areas in AS’s stronghold of southern Somalia.

Prior to field data collection, it was clear that AS’s response to COVID-19 had been very limited. AS often uses media to showcase the ways in which it helps the population in areas under its control: for example, it publicizes mediation successes between warring Somali clans, or publishes articles and photos showing its militants distributing aid to people in need, usually in the form of food or cash.

However, throughout the spread of COVID-19, AS has demonstrated a surprising lack of coverage about its own measures against the virus. When COVID-19 began spreading in Somalia earlier this year, pro-AS media channels focused simply on reporting on the spread of COVID-19 in Somalia and western countries, such as the United States, and it did not release its first statement directly addressing COVID-19 until April 27, when AS spokesman Mahamud Rage, aka Ali Dhere, discussed the pandemic in an audio message. Rage stated that the disease was afflicted on “infidels” due to their oppression of Muslims, and warned listeners that the virus had been spread in Somalia through the soldiers of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and other foreign actors that support the FGS in the fight against AS. Rage also criticized the actions taken by the FGS against COVID-19, stating that the FGS was following the example of disbelievers (reportedly referring to western governments) and putting pressure on Somali citizens by closing mosques and schools, and restricting the population’s movement.

Pro-AS media sources continued criticizing the reactions of the FGS and allied governments against COVID-19, but it was not until mid-May that AS publicized its first course of action to fight the virus. The group announced the creation of a committee, made up of doctors, religious scholars, and intellectuals, tasked with creating solutions to curb the spread of COVID-19. After this announcement, the next and only other action the group has taken was to set up a COVID-19 “prevention and treatment center” in Jilib, one of its major strongholds in Somalia, in mid-June. Data collected from civilians living in Jilib presents a different picture, with most affirming a severe lack of healthcare and prevention services available. Recognizing that data from 15 respondents is not statistically representative of the entire population, the finding still highlights AS’s inability to provide the necessary services to the population living in areas under its administration.

Testing, Equipment and Capabilities

Overall, respondents reported a complete lack of preparedness and ability to provide treatment and testing to those affected by COVID-19 in AS-controlled areas, despite the alleged existence of the COVID-19 treatment center in Jilib. Almost all respondents indicated that healthcare facilities in their area were not equipped to deal with the virus, while all respondents stated that it would be difficult for them to access testing. This lack of adequate resources to respond to the pandemic is not surprising, considering that Somalia as a whole is underprepared to deal with the virus. Furthermore, all respondents asserted that NGOs are not providing support to combat COVID-19 in AS-controlled areas, further disadvantaging those populations. In the past, humanitarian agencies have struggled to work in AS-controlled areas due to arbitrary taxation, strict surveillance, and threats of expulsion.

Preventative Measures and Awareness

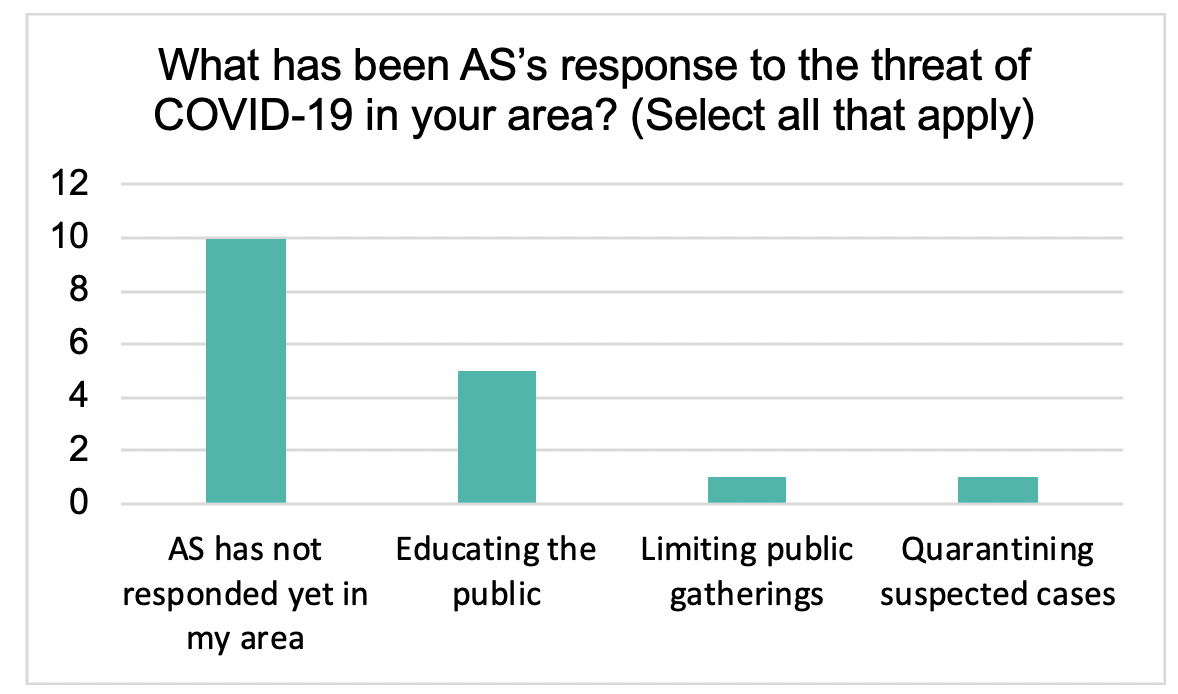

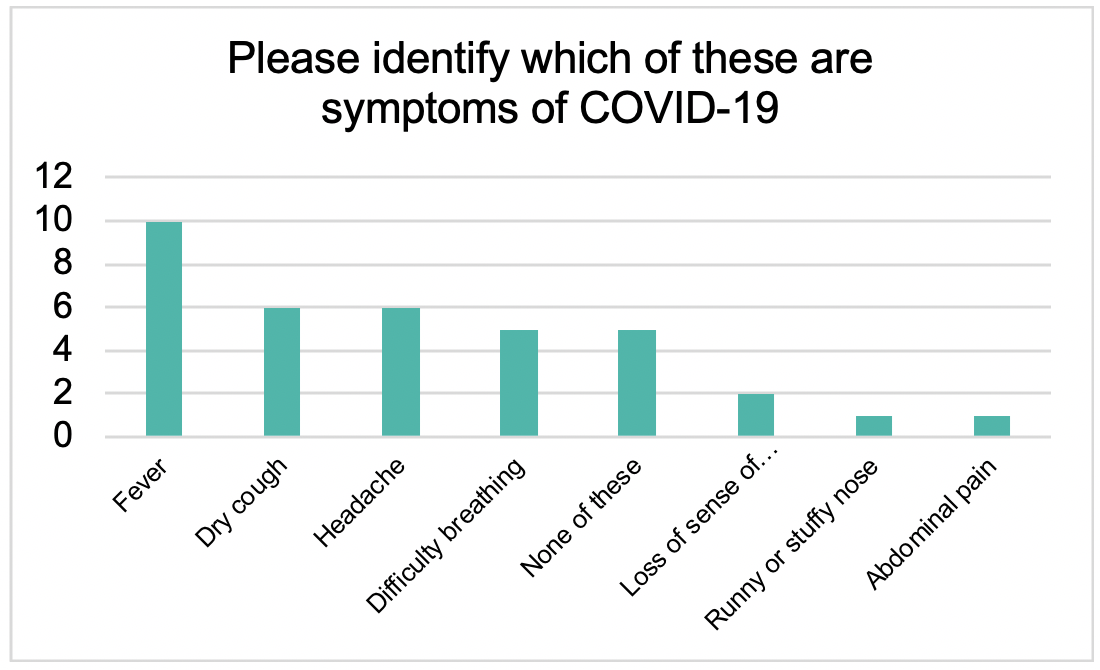

Although enforcing preventative measures and providing the population with information about COVID-19 could have eased the pressure from AS’s insufficient capabilities, the group does not seem to have prioritized these efforts. Notably, the only respondents who affirmed that AS had responded in their area, mostly through educating the public about the virus, were from Kunyo Barrow, Lower Shabelle region. Kunyo Barrow’s relative proximity to Mogadishu, the main COVID-19 hotspot in Somalia, may have driven AS’s slightly greater efforts to educate the population about the risks of COVID-19, although the group’s response remains very limited. When asked to identify the symptoms of COVID-19, a third of respondents indicated that none of the symptoms suggested were COVID-19 symptoms. While this level of knowledge about the virus may not be representative of the general population in AS-controlled areas, this highlights a heightened potential for spread, compounding the risk of asymptomatic transmission that is prevalent with COVID-19. A population that is uneducated about the symptoms of the virus is even more likely to spread it, putting additional strain on the underequipped healthcare capabilities of AS-controlled areas.

Additionally, all respondents indicated that AS had not closed any public spaces, including mosques, schools, or markets. Although both AS and the FGS allowed mosques to remain open during Ramadan, AS chose not to implement a curfew that would have prevented people from congregating to pray the evening prayer and break their fast together, like the FGS attempted to do. Furthermore, the lack of other preventative measures reported by respondents, who stated that AS did not provide masks, gloves, or hand sanitizer, may have only exacerbated the gravity and the spread of the virus in AS-controlled areas.

Outlook: What Does This Mean for the Fight Against AS?

AS often uses its propaganda to present itself as a better governing body than the FGS. It does so by criticizing the government’s policies, its allies, and portraying the FGS as a danger to the Somali population, while displaying the alleged quality of life that people enjoy in AS-controlled areas. However, life-threatening crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic severely hamper AS’s ability to sell itself as a better option for Somalia. This likely explains why its coverage of its own policies to handle the virus has been so limited—the group has preferred to focus on blaming the FGS and its allies, particularly AMISOM, for allowing the virus to enter Somalia and spread throughout the country, thereby reinforcing its narrative that foreigners are a danger to Somalia and strengthening its image as a Somali-focused group. While this strategy does not harm AS’s image, the lack of policies and defined actions to deal with the virus will damage its ability to present itself as a legitimate governing entity in the medium term.

This damage to the group’s legitimacy may only be exacerbated as the disease spreads across AS-controlled areas and as the group continues to conduct attacks against pro-FGS forces. If victims of COVID-19 increase dramatically as a result of a lack of adequate healthcare, the group’s mission to expand its territory may be seen as irrelevant or a waste of resources, while the cost in health and lives will directly affect its credibility as a political alternative. This may not have a significant effect on the group’s hold over people and territory in the short-term, as most of the population living under AS are unlikely to legitimately support the group, and instead are likely to live in its territory due to fear, but it may affect the group’s recruitment and expansion abilities in the medium- to long-term. More broadly, previous Navanti field data collection within AS-controlled communities in the past five years has consistently highlighted lack of medical services as a chief concern and complaint against AS among local residents.

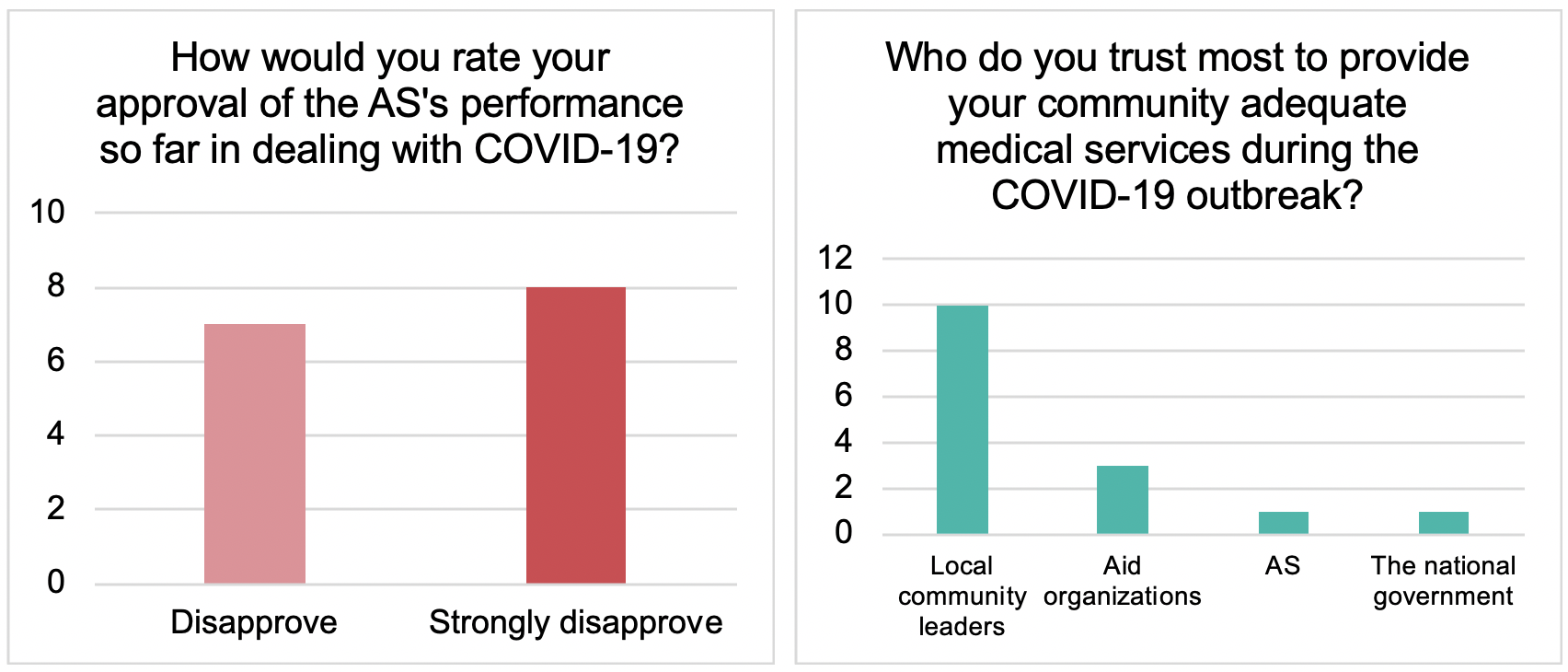

Notably, however, respondents reported similarly low levels of trust in both the FGS and AS to provide adequate medical services; most instead trusted local community leaders. While the FGS’s record in combatting COVID-19 has not been exemplary, recognizing this preference may provide an opportunity for the FGS to work with trusted community and clan leaders, who can relay valuable information to the population and attempt to implement better preventative measures against the disease. Conversely, AS has a similar opportunity, and has been known to attempt to co-opt clan leaders and elders in the past. The FGS must seize the initiative to strengthen these relationships and reach communities in a more direct way, in order to maximize preventative measures while blocking AS from building allegiances and direct ties to local communities.