By Johannes Claes and Rida Lyammouri with Navanti staff Published in collaboration with Clingendael

Niger could see its first democratic transition since independence as the country heads to the polls for the presidential election on 27 December. [1] Current President Mahamadou Issoufou has indicated he will respect his constitutionally mandated two-term limit of 10 years, passing the flag to his protégé, Mohamed Bazoum. Political instability looms, however, as Issoufou and Bazoum’s Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism (PNDS) and a coalition of opposition parties fail to agree on the rules of the game. Political inclusion and enhanced trust in the institutions governing Niger’s electoral process are key if the risk of political crisis is to be avoided. Niger’s central role in Western policymakers’ security and political agendas in the Sahel — coupled with its history of four successful coups in 1976, 1994, 1999, and 2010 — serve to caution Western governments that preserving stability through political inclusion should take top priority over clinging to a political candidate that best represents foreign interests.[2] During a turbulent electoral year in the region, Western governments must focus on the long-term goals of stabilizing and legitimizing Niger’s political system as a means of ensuring an ally in security and migration matters — not the other way around.

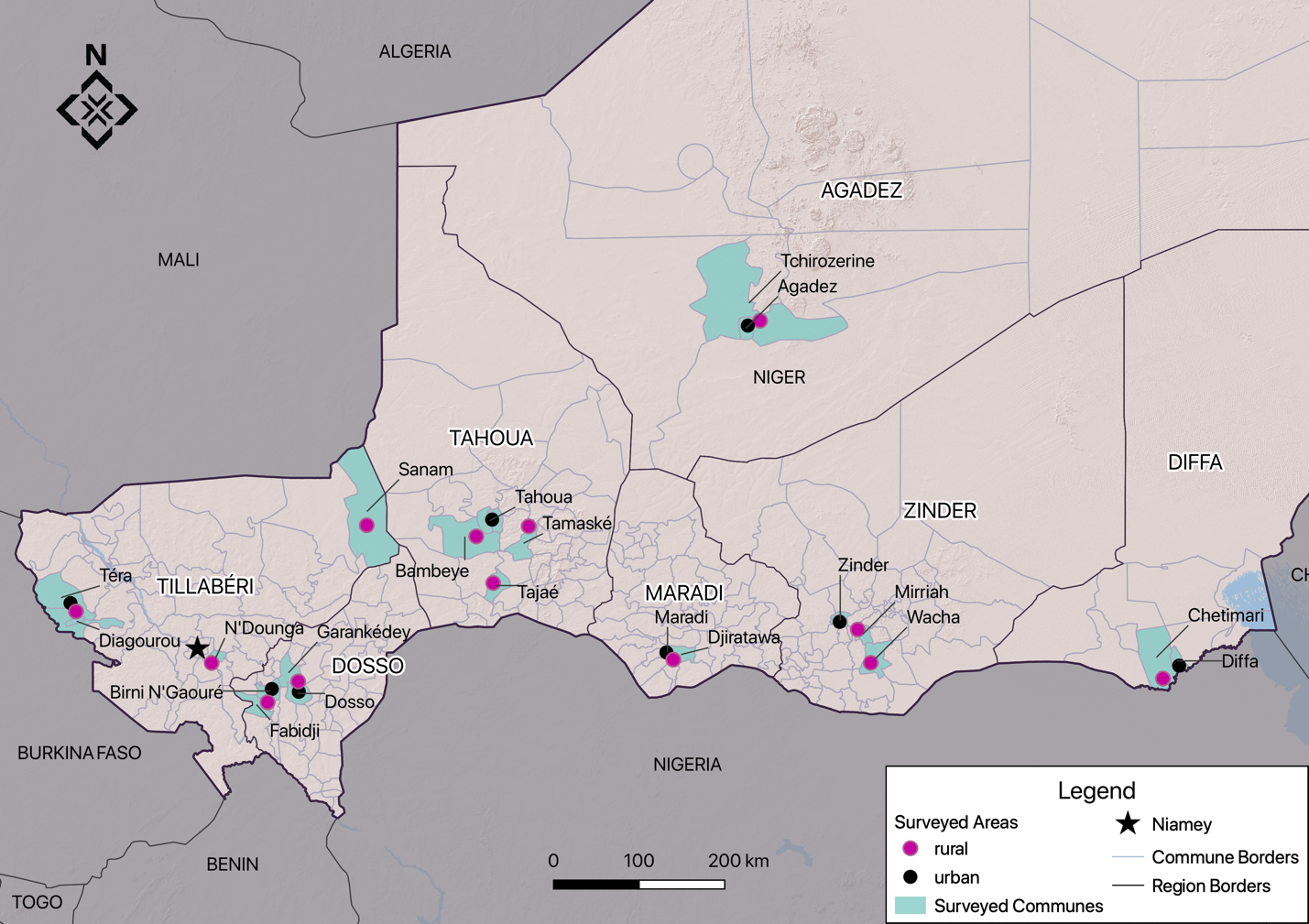

In order to better understand the perceptions and concerns of Nigériens in the run up to these elections, the Clingendael Institute and Navanti partnered to conduct data collection and analysis throughout all seven regions and the capital district. The Clingendael Institute interviewed 10 local political figures, from both the current administration and opposition parties, in the capital Niamey and the key northern city of Agadez; Navanti surveyed 403 residents outside Niamey, in order to focus on the view from the regions rather than the capital, applying a quota sample proportional by gender and by urban/rural settlement across the seven regions.[3] Both the interview guides and survey questionnaires focused on the electoral process — whether the upcoming elections would be free and fair, free of corruption or violence, and accepted without disorder — and perhaps more importantly, what impact the elections and incoming government will have on the biggest problems currently facing the country, such as unemployment, education, healthcare and insecurity. This article will lay out some of the key stumbling blocks that lie ahead in the electoral process before moving to what is at stake during these elections by zooming in on the expressed concerns of surveyed and interviewed respondents.

Photo: supporters greet leading presidential candidate Mohamed Bazoum at a rally in Agadez, Source: Souleymane Ag Anara

Map of the survey sample showing urban and rural data collection locations across all seven regions, Source: Navanti

Disagreement over election modalities

A serious hindrance to Niger’s future political stability is the lack of consensus between the ruling party and the opposition about the modalities under which the presidential elections should take place. The electoral code has been a source of tension and does not have the backing of the opposition. The voter roll similarly does not have their approval, as it excludes Nigériens living abroad. Finally, the composition of the two key institutions that can certify the elections and deal with any issues that arise, the Constitutional Court and the CENI, is a highly debated topic, as both bodies are seen by the opposition as politicized and favoring the ruling party. An interviewed opposition member expressed doubts about the impartiality of the CENI: “It’s all fixed and the CENI is always with them [the ruling party]. You know very well that some parties are not included in the composition of the CENI. Under such conditions it will be very difficult for elections to be free and fair.”[4]

The fiercely debated issue of independent electoral bodies is not a standalone issue of instrumentalization of state power in Niger. President Issoufou’s second term has seen a steady rise of repressive politics that have been criticized heavily by civil society and opposition parties. Protests in the capital over the past years have in many instances resulted in arrests of key civil society leaders. The most recent example is the incarceration of activists during a protest in Niamey against an alleged corruption scandal at the Defense Ministry.[5] Rights groups have decried such repressive tactics, as well as the growing arsenal of legal instruments at the disposal of the government to justify their interventions.[6]

Most interviewed opposition politicians express their concern that the elections will not take place in a free and fair manner. The opening of formal campaigning on 5 December took place against the backdrop of a decision of the Constitutional Court of 13 November to invalidate the candidacy of leading opposition figure Hama Amadou.[7] The Court ruled that Amadou, who has been in a legal battle with the Nigerien justice system over an alleged child-trafficking case, in which he was condemned to one year in prison, is ineligible as candidate for the highest office in Niger based on Article 8 of Niger’s electoral code. The article bars citizens convicted of crimes with prison sentences of one year or more from running for president.[8]

For opposition members, this stands in sharp contrast to the ruling of the Court one week later, in which it rejected the challenge to PNDS candidate Bazoum’s eligibility that had been the focus of much debate in Niger’s political scene on the basis of doubts around his nationality.[9] The ruling revolved around Article 47 of the Constitution, which stipulates that only those with Nigérien nationality are eligible for the office of the president. The court ruled that doubts around Bazoum’s nationality were ill-founded and considered the case closed in its ruling. This lays bare the reasons why interviewed participants don’t believe Niger’s electoral process to be free and fair. Institutions are perceived as politicized and favoring the ruling party and its allies, while deliberately excluding opposition figures seeking to take part in electoral processes.

One opposition member reflected on the Court decision relating to Hama Amadou, “The refusal is about one single person, Hama Amadou. He is a citizen and enjoys all of his rights. The case is purely political, whether you want it or not.”[10] On the court’s decision on PNDS candidate Bazoum, the same opposition interviewee added, “The candidate of the ruling party is dubious because this is someone who has two nationalities, obtained in 1985 when we were all at school, and he himself was studying in Senegal. Why are we not talking about him?”[11] Another opposition member expressed hopes that Amadou would still be able to compete in the elections: “To be clear, for me, they need to let Bazoum and Hama Amadou compete against each other.

That would be the right thing to do, and only then will we see who is loved by the people. If they’re not afraid of Hama, they should accept his candidacy and appease tensions, and then may God give us a good boss between the two of them.”[12]

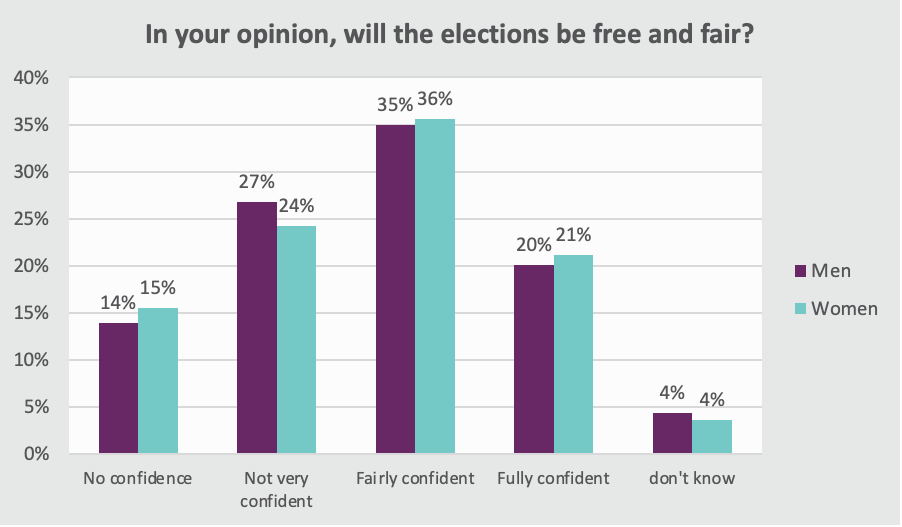

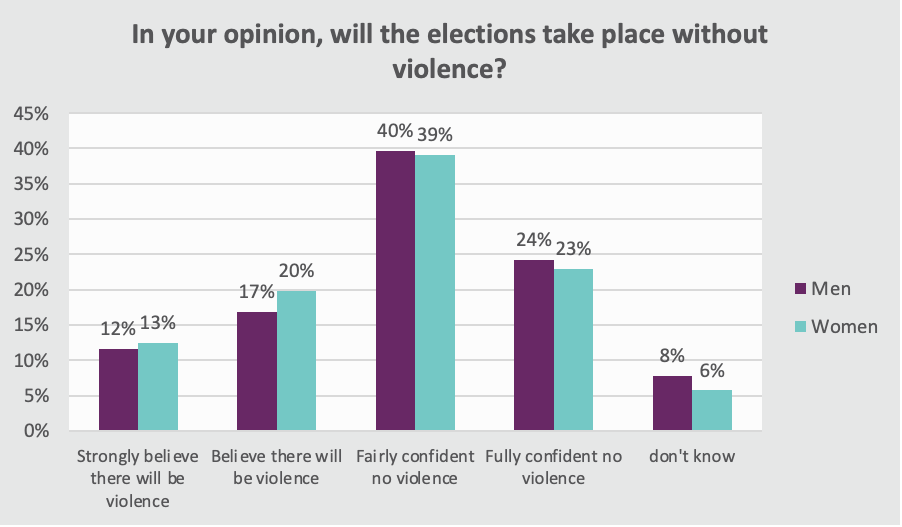

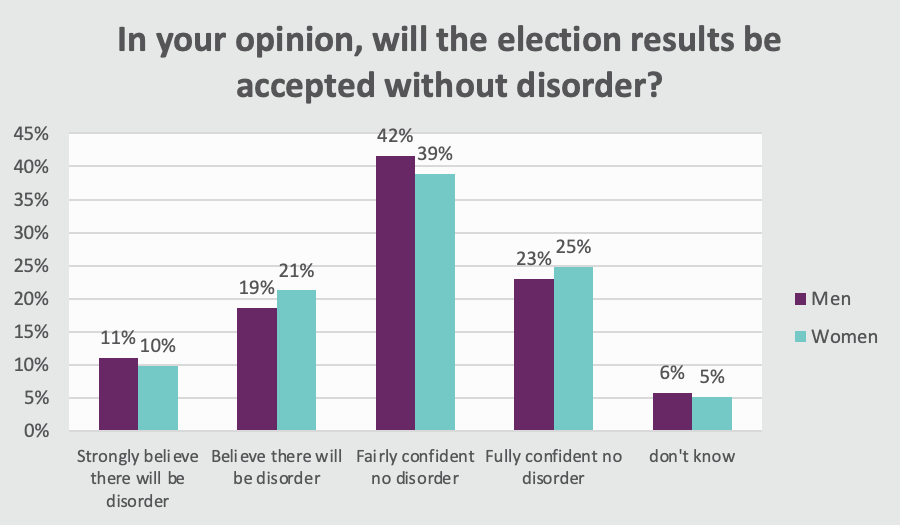

While survey respondents showed less worry that the elections will take place in a free and fair manner, overall 40% nevertheless expressed doubts. Similarly, about 30% of respondents expressed doubts that the elections would lead to changes within their community.

Opposition in disarray?

In 2016, the opposition parties were unified under the Coalition for Alternance 2016 (Copa 2016), and they boycotted the second round of the election, accusing the process of being fraudulent. The move benefitted Issoufou, who won the second round with 96% of the vote and left the opposition largely excluded from any political process. This year, to improve their chance against the ruling party, 18 opposition parties have come together in a new alliance called Cap 21 and have promised to support the candidate who achieves the best result in the first round during the second round.

Therefore, although Hama Amadou’s candidacy has been barred, this does not mean that his electorate is completely disenfranchised. It is likely that the opposition will rally around another candidate and while it is unclear at this stage what the final strategy of the opposition parties will be, they seem committed to partake in the electoral process. [13] [14] Signaling such a departure from the more passive attitude in 2016, earlier this week 2010 coup leader and current presidential candidate Salou Djibo announced that he will be taking the matter of Bazoum’s nationality back to the Constitutional Court and denounced the Court’s handling of the case in the 19 November ruling.[15]

Whichever candidate the opposition decides to support, it will need to force a run-off in a second round if it wants to beat the PNDS, whose strategy is based on winning the presidency in the first round. Analysts have pegged Bazoum as the most likely candidate to win the presidential elections. Among surveyed respondents, Bazoum was cited as the most likely winner in many regions – although a majority of respondents in Dosso and Diffa and a plurality in Maradi did not name a candidate (either “don’t know” or “prefer not to answer”).[16] Some analysts have pointed out, however, that a strong coalition forming among opposition parties in a potential second round might provide the opposition with enough support in the regions to turn the chances of a PNDS victory.[17] Bazoum’s lack of an electoral stronghold – such as Issoufou’s Tahoua region or Hama Amadou’s support in Niamey – might turn out to be an obstacle.[18]

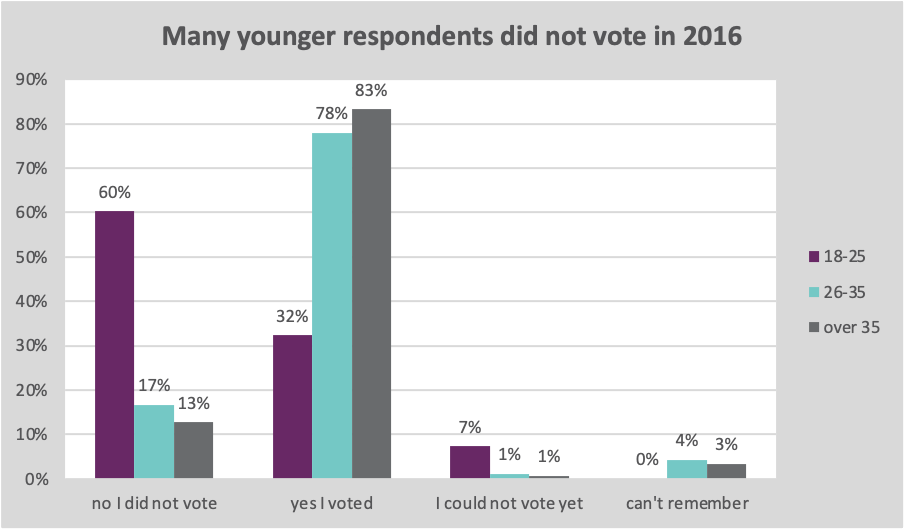

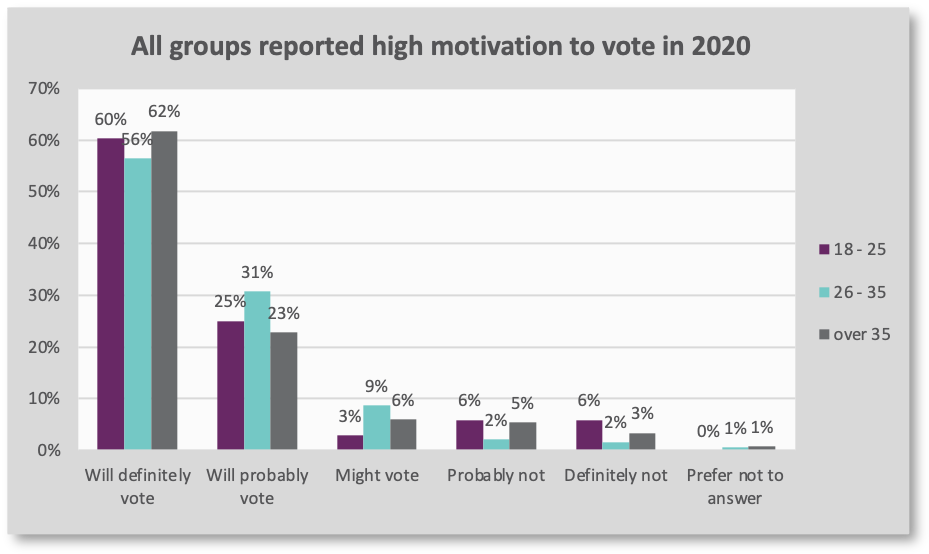

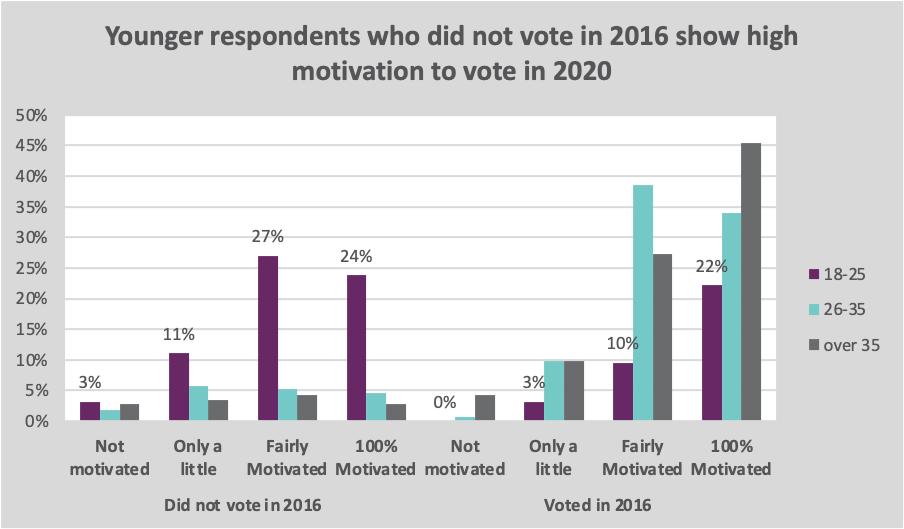

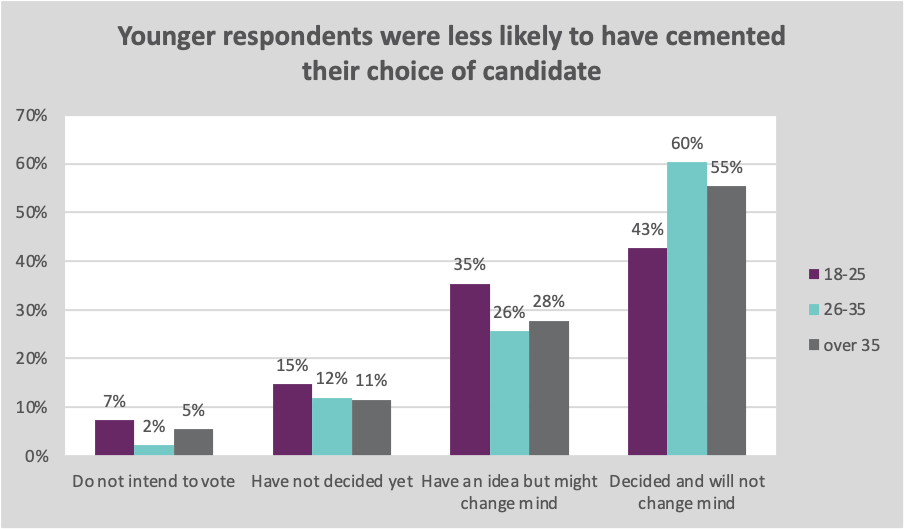

Within our survey sample, 56% of respondents overall reported that they have already decided who they will vote for and will not change their mind. Respondents age 18-25 were most likely to report that had either had not yet decided on a candidate or may change their mind. Overall, a majority of those who reported they did not vote in the 2016 election (by choice, and not because they were too young to vote) reported that they do intend to vote in the upcoming election, a swing observed most strongly among respondents 18-25. This shift in motivation and intention to participate among the younger electorate, coupled with less predictability for their choice of candidate, could impact voting tallies, though perhaps not largely enough to impact ultimate outcomes.

|

In your opinion, who will win the election? |

Agadez |

Diffa |

Dosso |

Maradi |

Tahoua |

Tillabery |

Zinder |

Grand Total |

|

Mohamed Bazoum |

58% |

43% |

13% |

18% |

52% |

39% |

40% |

35% |

|

Do not know |

8% |

57% |

40% |

29% |

1% |

24% |

2% |

18% |

|

Albadé Abouba |

25% |

0% |

10% |

8% |

30% |

6% |

18% |

15% |

|

Mahamane Ousmane |

0% |

0% |

2% |

13% |

2% |

3% |

30% |

11% |

|

Ibrahim Yacouba |

0% |

0% |

4% |

15% |

9% |

11% |

3% |

8% |

|

Prefer not to answer |

0% |

0% |

31% |

2% |

1% |

5% |

3% |

6% |

|

Seini Oumarou |

0% |

0% |

0% |

7% |

5% |

6% |

1% |

4% |

|

General Salou Djibo |

0% |

0% |

0% |

8% |

0% |

6% |

2% |

3% |

|

Other |

8% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

1% |

0% |

|

Grand Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Development challenges

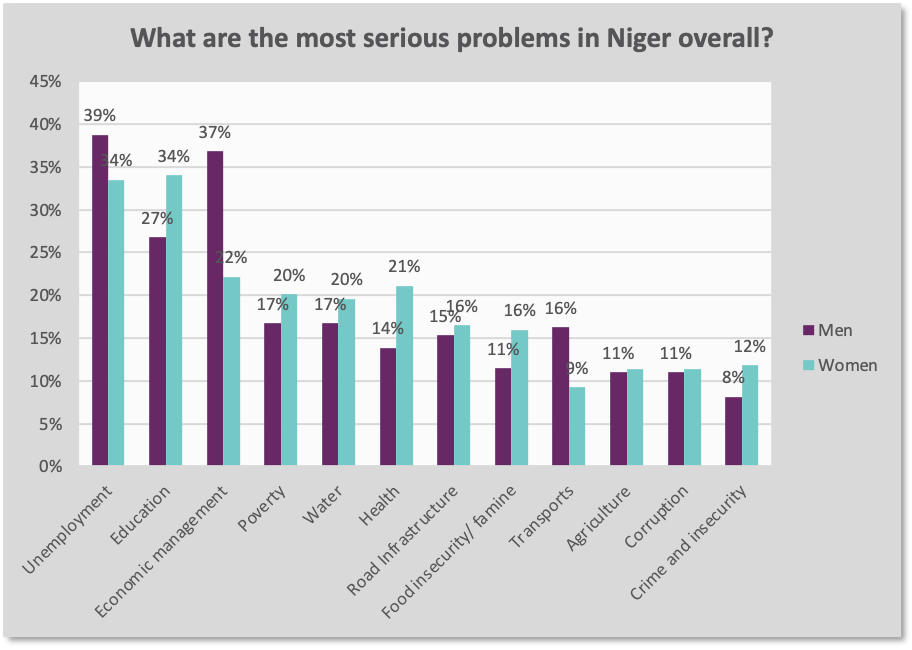

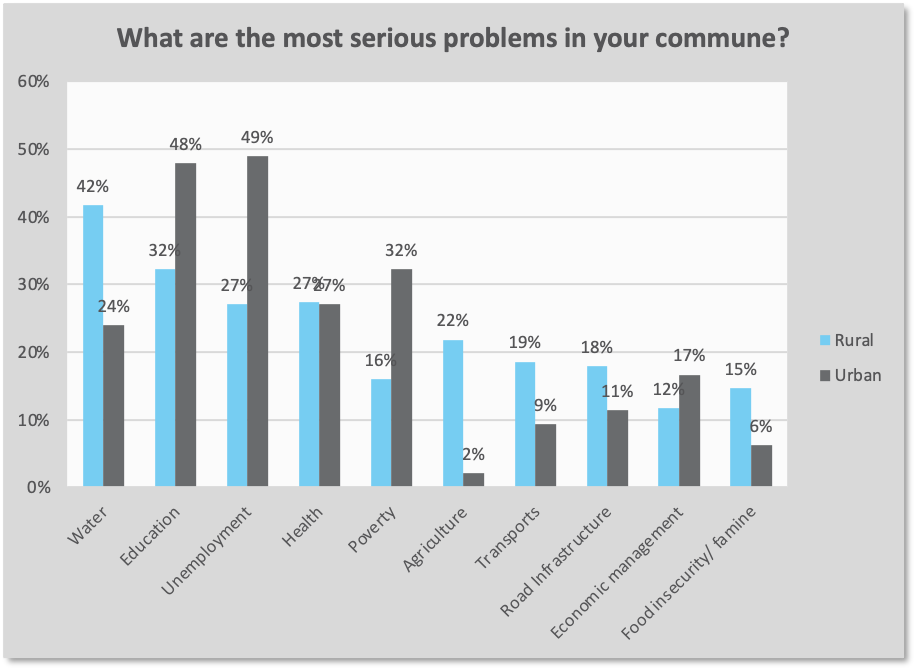

What is at stake for Nigériens in these elections? Structural development challenges — not crime or insecurity — dominated surveyed respondents’ top concerns in their communities and the country as a whole. Respondents most frequently listed issues like unemployment, education, water and road infrastructure, and healthcare as the most serious problems, which are likely to remain key challenges for the next administration. While much focus has been placed on prestigious projects in the capital, Niamey, such as bridge and road infrastructure and a new international airport,[19] opposition figures blame Issoufou’s administration for the lack of investment into the country’s education and healthcare systems.[20]

The commitment of the state to invest significantly in development is called into question in the context of a national budget that sees relatively low amounts of funding set aside for public health and education.[21] While the dedication of a large part of its budget to defense spending signals that concerns about insecurity are taken seriously, corruption scandals in defense contracting that broke earlier this year cause many to doubt the true beneficiaries of such funds, which seems to come at the expense of ordinary soldiers deployed in the volatile border regions.[22] One opposition interviewee commented: “The investigation has shown that people have misappropriated billions [of francs CFA] that were intended for the army, and these people are not even being bothered about this. Our army needs to be [made] capable to face the challenges it has before it by creating the conditions and giving it top notch equipment.”[23] Civil society has been vocal on social media about the vast amounts of money set aside for the presidential administration, as opposed to the education and healthcare ministries.[24] While surveyed respondents did not place corruption high on their list of prominent issues, the matter has the potential to mobilize many in Niamey, where political dynamics favor popular action (such as street protests) against corruption and, more importantly, where the opposition enjoys an historic majority.[25]

Photo: Supporters surround Bazoum during his rally in Agadez, Source: Souleymane Ag Anara

Security concerns

Interview respondents stressed that security will need to be a key priority for the new administration. While survey respondents seemed less inclined to rank it among Niger’s top issues (10% of respondents), the Tillaberi, Tahoua, and Diffa regions continue to struggle with insecurity tied to violent extremist organizations (VEOs) that seems to be worsening despite ongoing military operations. VEO attacks against the country’s Defense and Security Forces (FDS) are on the rise, as are violent actions committed by state security forces. The government’s efforts to tamp down the spiraling violence have produced very little — if any — tangible results. A strategy of militarization of border zones has further stigmatized already fragile border communities while failing to address the local conflicts that insurgent groups appropriate to gain influence. The violence is also exacerbated by natural disasters, both cyclical and unique in nature. The combination of violence, floods, COVID-19, and increasingly long dry seasons resulting from climate change has left more than 3.7 million people in need of humanitarian assistance in Niger and displaced an estimated 226,000 people.[26],[27] Members of the ruling party and the opposition stressed in their interviews that solving the dire security situation should be a top priority for the incoming administration.

One opposition politician said, “When a state that cannot guarantee the security of its citizens, that’s an issue. Our soldiers are getting killed like flies.” A PNDS member commented, “The most urgent problem for me, is first and foremost the security problem. We have an extremely strategic position, Libya on one side, and then Nigeria, Chad and Mali. We have to try and secure the people.”[28] Security played only a small role in the preparations for the elections until a VEO attack killed 27 people in the village of Toumour, Diffa region, on the eve of the municipal elections on 12 December, destroying the majority of the village.[29] Up to this point, the preparations had thus far been largely peaceful except for an attack in December 2019 that targeted a convoy of the National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI) officials in Tillaberi region in which 14 soldiers were killed.[30] The aftermath of the Toumour attack might weigh on voter participation in Diffa as well as on other border regions that have been in prolonged state of emergency due to the worsening security climate. In addition, it is likely that voting will be complex if not impossible for Niger’s over 220,000 internally displaced people.[31]

Conclusion

The relative calm around Niger’s local elections does not mean the country is out of the woods. The lack of consensus between the opposition and the ruling party on the rules of the game in the presidential elections, especially with regards to the eligibility of political leaders and the country’s institutions, is a threat that may result in political instability and weigh on the country’s social cohesion. Analysts have already noted that mass post-electoral violence is unlikely.[32] What is at stake, however, is confidence in political institutions in Niger, which is likely to be further undermined if the race is not perceived as free and fair.

This will pose a risk to Niger’s political stability, if not in the short term, then certainly in the long term. The fact that Issoufou is willingly leaving the political scene after his two constitutionally allowed mandates, in contrast to his recently deceased predecessor, Mamadou Tandja, does not negate that for many in the opposition, five more years of PNDS rule will be tough to stomach. Additionally, the fact remains that PNDS is likely to stay in power, which will not create the conditions under which Issoufou’s policies and corruption scandals are likely to be held to account. Continued government refusal to address corruption and failed development policies will further feed a lack of trust in state institutions.

The PNDS has the upper hand and its militants seem confident that they will deliver the next president which is in line with survey data. Opposition parties in Niger may however fare better in these elections than they did in 2016, as they are unlikely to repeat the mistake of boycotting the process. Although the opposition parties have been seemingly thrown into disarray with the invalidation of Hama Amadou’s candidacy, many opportunities for coalition building remain, especially if the vote is decided in a second round in February 2021.

These dynamics seem at the time of writing to mostly cast doubt, before actual ballots. Many Western states have an interest in the outcome of the Nigérien election due to Niger’s status as a key regional partner, and its role in security and migration. Yet this does not need not prevent international partners from also encouraging the strengthening of democratic institutions, transparency and accountability, in response to legitimate concerns voiced by Nigerien citizens. Above all, despite the considerable funding that has gone into the country in the last decade, much still remains to be done. Democratic norms and transitions of power have to be fostered, while paying attention to basic needs of Niger’s young and growing population in terms of healthcare, social and economic inclusion, ecology, and community security.

|

2016 Elections Results by |

||||||||||

|

Political Party |

Agadez |

Abroad |

Diffa |

Dosso |

Maradi |

Niamey |

Tahoua |

Tillabery |

Zinder |

Total |

|

PNDS TARAYYA |

64% |

52% |

46% |

32% |

37% |

25% |

81% |

31% |

33% |

46% |

|

MODEN FA LUMANA AFRICA |

9% |

37% |

17% |

23% |

7% |

44% |

6% |

41% |

5% |

16% |

|

MNSD NASSARA |

18% |

11% |

16% |

10% |

16% |

11% |

5% |

19% |

16% |

13% |

|

MNRD HANKURI AND PSDN ALHERI |

4% |

0% |

3% |

3% |

4% |

3% |

0% |

4% |

18% |

5% |

|

MPN KIISHIN KASSA |

2% |

0% |

1% |

18% |

4% |

8% |

2% |

3% |

0% |

4% |

|

RSD GASKIYA |

0% |

0% |

1% |

1% |

8% |

1% |

4% |

0% |

6% |

4% |

|

CPR INGANCI |

1% |

0% |

1% |

1% |

12% |

2% |

1% |

1% |

2% |

3% |

|

CDS RAHAMA |

1% |

0% |

10% |

5% |

6% |

1% |

0% |

0% |

5% |

3% |

|

UDR TABBAT |

0% |

0% |

3% |

7% |

2% |

4% |

1% |

1% |

6% |

3% |

|

ARD ADALTCHI MUTUNTCHI |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

1% |

1% |

1% |

0% |

9% |

2% |

|

CDP MARHABA BIKHUM |

0% |

0% |

1% |

0% |

1% |

0% |

0% |

1% |

1% |

0% |

|

MDR TARNA |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

1% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

|

Grand Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Region

% of survey pop.

% urban

% rural

# urban

# rural

Total

|

Agadez |

3% |

50% |

50% |

6 |

6 |

12 |

|

Diffa |

3% |

29% |

71% |

4 |

10 |

14 |

|

Dosso |

13% |

19% |

81% |

10 |

42 |

52 |

|

Maradi |

22% |

31% |

69% |

27 |

60 |

87 |

|

Tahoua |

20% |

26% |

74% |

21 |

60 |

81 |

|

Tillaberi |

16% |

8% |

92% |

5 |

61 |

66 |

|

Zinder |

23% |

25% |

75% |

23 |

68 |

91 |

|

Overall |

100% |

24% |

76% |

96 |

307 |

403 |

About the Authors

Johannes Claes, Research Fellow at Clingendael Institute, @JohannesClaes

Rida Lyammouri, Associate Fellow at Clingendael Institute, @rmaghrebi

References

[1] A second round is possible on February 21st 2021.

[2] Oxford University Press, “The 2010 coup d’état in Niger: A praetorian regulation of politics?,” 11 April 2011, https://academic.oup.com/afraf/article-abstract/110/439/295/164122

[3] Annuaire statistique du Niger 2018, via UNOCHA: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/niger-other/resource/ab22d184-52f3-4e2f-bbfd-c21e0a7c3d9f and Republique du Niger, Ministere de l’Interieur,

[4] Interviews in Niamey and Agadez, November 2020.

[5] Amnesty, “Niger: Human Rights Defenders Still Unjustly Detained for More than Six Months,” accessed November 5, 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/09/niger-trois-defenseurs-des-droits-humains-injustement-detenus/?fbclid=IwAR0n1AmiRwfU1ReKa-MbtZ9oFOr_GiUb-tByDDWvHAT403IUSeVQMQ0vxO8.

[6] Amnesty, “Niger. Le Prochain Président Devra Agir sans Délai pour Renverser la Tendance en Matière de Droits Humains,” 11 December 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/fr/latest/news/2020/12/niger-le-prochain-president-devra-agir/

[7] Cour Constitutionnelle, Accessed 30 November 2020, http://www.cour-constitutionnelle-niger.org/documents/arrets/matiere_electorale/2020/arret_n_05_20_cc_me.pdf

[8] Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI), Code Electoral, Mars 2020, https://www.ceniniger.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/code-%C3%A9lectoral-A6.pdf

[9] Cour Constitutionnelle, Accessed 30 November 2020, http://www.cour-constitutionnelle-niger.org/documents/arrets/matiere_electorale/2020/arret_n_06_20_cc_me.pdf

[10] Interviews in Niamey and Agadez, November 2020.

[11] Interviews in Niamey and Agadez, November 2020.

[12] Interviews in Niamey and Agadez, November 2020.

[13] TV5 Monde, “Présidentielle au Niger: Début de la Campagne Électorale sans Hama Amadou, le Principal Opposant,” 07 December 2020, https://information.tv5monde.com/afrique/presidentielle-au-niger-debut-de-la-campagne-electorale-sans-hama-amadou-le-principal

[14] Tatiana Smirnova, “Décryptage. Une Autre Présidentielle sous Tension en Afrique de l’Ouest: le Cas Nigérien,” October 2020, Page 9, https://dandurand.uqam.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Bulletin-FrancoPaix-vol5n8.pdf

[15] Facebook, Accessed December 2020https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=1264217833951525&ref=watch_permalink

[16] Note that the survey sample did not include Niamey. For the first round election results in 2016 by region, see the table at bottom.

[17] Tatiana Smirnova, “Décryptage. Une Autre Présidentielle sous Tension en Afrique de l’Ouest: le Cas Nigérien,” October 2020, Page 9, https://dandurand.uqam.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Bulletin-FrancoPaix-vol5n8.pdf

[18] Despite his strong backing in Tahoua Issoufou was unable to secure a win in the first round of presidential elections in 2016.

[19] Niamey et les 2 Jours, “Niamey-Nyala : un Programme de Plus de 400 Milliards FCFA,” 19 October 2020, https://www.niameyetles2jours.com/l-uemoa/infrastructures/1910-6031-niamey-nyala-un-programme-de-plus-de-400-milliards-fcfa

[20] Niger has tended to rank last or next to last on the Human Development Index composite of life expectancy, income, and education, since the index’s inception. Its 24 million population is rising fast as are its development needs. More than half of the population is under 15-year-old, and the average years of schooling are 6.5 years which is compared to neighboring countries (7.6 in Mali and 8,9 in Burkina Faso). The enrollment rate in school is 62% for girls and 71 for boys.

[21] Ministere of Finance, “Texte de Projet de Loi de Finances 2021 au 17 septembre 2020,”

Accessed December 2020, http://www.finances.gouv.ne/index.php/lois-de-finances/file/675-texte-de-projet-de-loi-de-finances-2021-au-17-septembre-2020

[22] Jason Burke, “Niger Lost Tens of Millions to Arms Deals Malpractice, Leaked Report Alleges,” the Guardian, August 6, 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/06/niger-lots-tens-of-millions-to-arms-deals-malpractice-leaked-report-alleges.

[23] Qualitative interviews in Niamey and Agadez, November 2020.

[24] Facebook.com, Accessed December 2020, https://www.facebook.com/moussa.tchangari.54

[25] Jeune Afrique, “Niger: Une Manifestation Contre la Corruption Dispersée à Niamey Après son Interdiction par les Autorités,” 10 May 2017, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/436616/politique/niger-manifestation-contre-corruption-dispersee-a-niamey-apres-interdiction-autorites/

[26] “Protection Civile et Operations d’Aide Humanitaire Européennes – Niger,” European Commission, December 19, 2013, https://ec.europa.eu/echo/where/africa/niger_fr

[27] UNHCR, “Situation Sahel Crisis,” accessed October 26, 2020, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/sahelcrisis

[28] Qualitative interviews in Niamey and Agadez, November 2020.

[29] Le Point, “Niger: Nouvelle Attaque Sanglante dans la Région de Diffa,” 14 December 2020,

[30] Radio France International (RFI), “Niger: Quatorze Militaires Tués Lors d’une Embuscade dans la Région de Tillabéri,” 26 December 2019, https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20191226-attaque-niger-quatorze-militaires-morts-embuscade-tillaberi

[31] Alex Thurston, “Key Upcoming Dates in Niger’s Electoral Calendar,” 01 September 2020, https://sahelblog.wordpress.com/2020/09/01/key-upcoming-dates-in-nigers-electoral-calendar/

[32] Alex Thurston, “Niger: Context on the Rejection of Hama Amadou’s Candidacy,” 16 November 2020, https://sahelblog.wordpress.com/2020/11/16/niger-context-on-the-rejection-of-hama-amadous-candidacy/