Coronavirus and GCC Resilience to 21st Century Threats

by Lindsay Carroll, Arabian Peninsula Analyst

In 2011, the self-immolation of a Tunisian vendor unexpectedly set off a wave of transnational unrest across the Middle East that has fundamentally changed political and security paradigms throughout the region ever since. Nearly 10 years later, the region faces what appears on the surface to be another “black swan” event, but it is not. Like the Arab Spring, COVID-19 will likely transform the region for years to come, and the economic crisis the pandemic has caused may challenge assumptions about nations’ resilience to 21st century threats.

After the Arab Spring, a narrative emerged that the protests showed the ability of the region’s monarchies, and especially the oil-rich Gulf states, to counter forces behind unrest not only at home but to shape outcomes elsewhere in the region. Though the Gulf states are also better equipped to handle COVID-19 than other countries in the Middle East, the novel coronavirus has still highlighted features of their economies that appear particularly vulnerable to pandemics.

These vulnerabilities are worth examining because the incidence of a pandemic such as COVID-19, though unexpected in timing, was widely predicted. Public health experts have long warned of signs of an increasing threat of infectious disease, which mean that the novel coronavirus is a harbinger of transnational threats for decades to come. As a prescient report warned last year: “While disease has always been part of the human experience, a combination of global trends, including insecurity and extreme weather, has heightened the risk. … there is a very real threat of a rapidly moving, highly lethal pandemic of a respiratory pathogen killing 50 to 80 million people and wiping out nearly 5% of the world’s economy.”

Climate change researchers and environmental security experts have also sounded the alarm because of links between infectious disease outbreaks and environmental trends. World Health Organization models have predicted that increasing rainfall variability, average temperatures, and humidity in some regions because of climate change could extend the range and transmission of diseases including malaria and dengue fever. Additionally, as the U.S. intelligence community’s Worldwide Threat Assessment highlighted last year, urbanization and human migration into unsettled land pose increase human contact with wildlife. This heightens the risk of viruses jumping from animals to humans, as occurred with the virus that causes COVID-19 as well as the SARS and MERS coronaviruses and ebola. Human displacement also has significant effects, and climate change is expected to force large-scale migration.

These risks show that challenges to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) economies could outlast COVID-19, especially if the pandemic spurs greater action to mitigate climate change. While the oil price slump of 2014 underlined the urgency of ambitious visions for national development and economic diversification, GCC countries remain highly reliant on oil. Though Qatar is chiefly reliant on natural gas and is no longer a member of OPEC, it remains impacted by increased competition in the natural gas market amid lower demand. Saudi Arabia reportedly needs an oil price of $80 a barrel for its budget to break even, but amid unprecedented low demand and concerns that global storage was reaching capacity, the price of Brent crude – the international benchmark – dropped below $20 on April 21. This has led some to fear that international prices could follow U.S. oil and approach near zero. Bahrain and Oman, both debt-ridden and suffering poor credit ratings, are the most vulnerable to the collapse in oil prices. Saudi Arabia’s price war flooding the market with an oversupply of crude oil and the kingdom’s purchases of cheap European oil assets show that it has attempted to mitigate the situation through long-term gains – undermining or reining in the U.S. shale industry and growing its sovereign wealth fund – but sustained pressure could still be damaging.

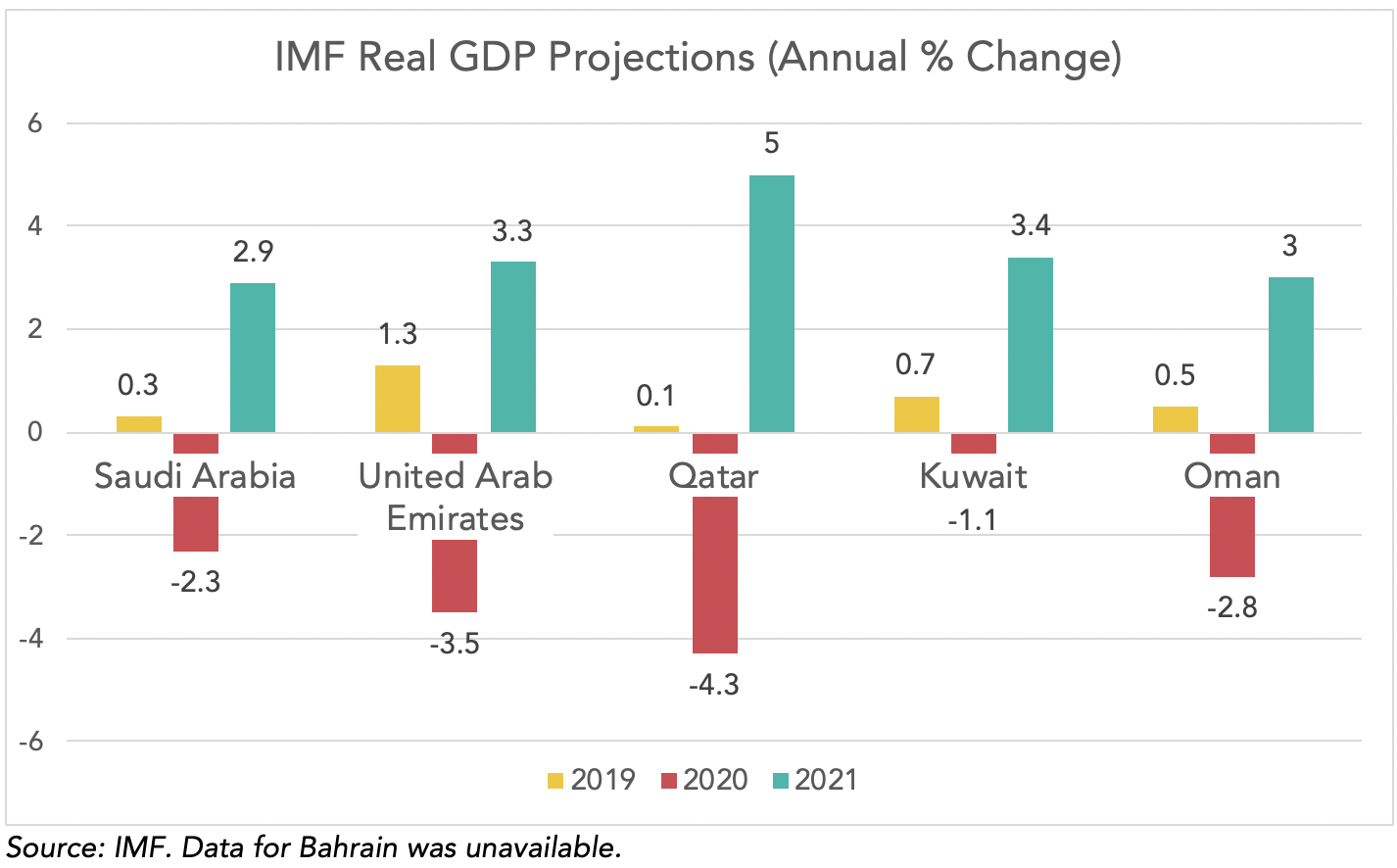

COVID-19 has also revealed that many of the GCC’s most important non-oil sectors, such as aviation, tourism, real estate, and trade and logistics, are also heavily impacted by disease outbreaks. The International Air Transport Association predicts air transport demand for Middle East airlines to decline by 51 percent in 2020 compared to the previous year, for example. Spending cuts could further reducegovernment support for non-oil sectors, while reductions in the foreign labor workforce as workers return home could have wide-ranging and potentially long-term effects on the domestic economy. These challenges show vulnerabilities exist even where GCC economies have successfully diversified. As non-oil revenues comprise nearly 60 percent of government revenues in the UAE, it perhaps best exemplifies this risk. Though this amounts to the highest proportion in the GCC, the International Monetary Fund still expects GDP to contract by 3.5 percent in 2020 – a higher percentage than Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Oman. These IMF projects may even be conservative.

As GCC economies seek to diversify and attract foreign investment through creation of global hubs of technological innovation and international commerce, COVID-19 may provide a lesson that such strategies could lock them in to the risks of associated with globalization, urbanization, and climate change. It could suggest other diversification sectors such as research, manufacturing, and investment in human capital are even more essential for maintaining resilience in the 21st century.