By Christa Waegemann

During the last six months, Iraq’s government has been under immense pressure due to simultaneous crises: social unrest, a dysfunctional and corrupt government, the growing spread of the coronavirus, and economic ruin. During the first week of April, the new Prime Minister designate, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, formerly Chief of National Intelligence, was given 30 days to form a cabinet, a goal the previous two designates failed to achieve. If Kadhimi is confirmed, he will face an overwhelming agenda to tackle immediate challenges within the country, including preparing Iraq for an early election. At the same time, the Iraqi government is struggling to respond to and contain the COVID-19 outbreak, particularly as the holy month of Ramadan begins. Although the protests that began in October 2019 have paused temporarily, al-Kadhimi must be pragmatic in acknowledging grievances and finding solutions that address their demands. Finally, for a government that is dependent on oil, the recent drop in oil prices will require Iraq to readjust its 2020 budget in order to pay salaries, a problem it faced during the economic crisis resulting from the Islamic State insurgency in 2014.

Response to COVID-19 outbreak and awareness

As of April 20th 2020, the Iraqi government had reported 1,539 cases and 89 deaths as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, which was first reported in the country in mid-February. Given that Iraq is rated 167 out of 195 on the Global Health Index, the number of cases is probably underreported due to the weak healthcare system decimated long before COVID-19 emerged. In response to the outbreak, the government has limited entry into the country by closing border crossings and airports. Schools and universities have also closed, and the government implemented a curfew to limit virus exposure and spread. The Kurdish Regional Government has also implemented strict rules, closing all government and public institutions until May 2nd. Yet, the population has at times violated the rules by attending religious and social events. A funeral in Erbil at the end of March led to around 41 new cases, 32 of which came from direct contact with one infected attendee. Generally, Iraq has a limited capacity for COVID-19 testing and follow-up, and observers also estimate that the country’s border with Iran has a higher level of undisclosed cases.

Baghdad Municipal Department workers sanitize a street in Jadriyah, Baghdad. Photo credit: Salam Khaleel.

Government restrictions

As highlighted above, in preparation for the holy month of Ramadan the Iraqi government has implemented a curfew from 7 p.m. until 6 a.m., thereby changing the usual traditions of iftar dinners that take place as families gather to break their fast. In addition, the Iraqi government released a set of guidelines requiring everyone to wear a mask when outside their house; those who do not wear them will be fined 50,000 IQD (approximately 42 USD). Government employees have also been reduced to working 1.25 days a week (25%).

In the Baladiyat neighborhood in Baghdad, the Ministry of Health supervises along with Baghdad Municipality neighborhood sterilization. The teams work in a 3 days shift, coming back to the same locations every 3 days to sterilize again. Photo credit: Ahmed Pasha Windi.

In addition to the general cautionary provisions, the Ministry of Health has implemented a range of supportive measures to address and curb the spread of the coronavirus. According to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the governments of Belgium, the Netherlands and Sweden also have committed 5 million US dollars to support Iraq’s COVID-19 response. This builds upon the UNDP’s initial $22 million response package focused on hospitals in Iraq’s most vulnerable communities, including those in Anbar, Diyala, Dohuk, Basra, Karbala, Najaf, Ninewa and Salah Al-Din.

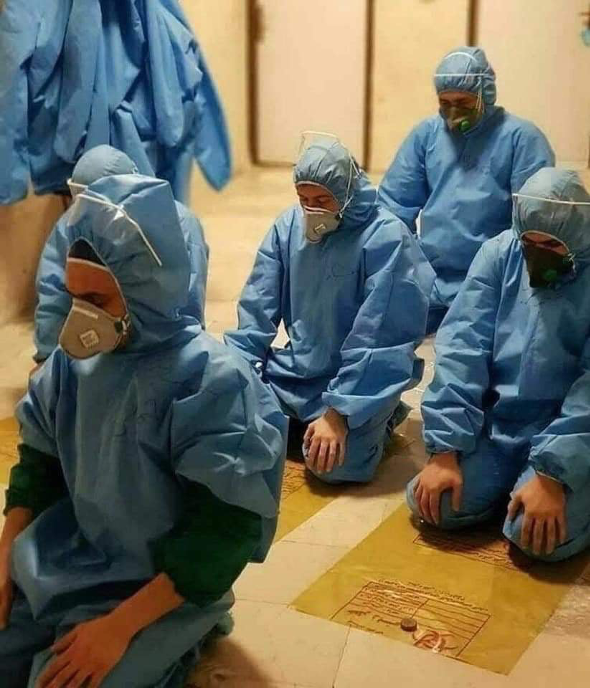

Mosul’s Al Shifaa Hospital, which ISIS used as one of its headquarters during the war in 2017 and was heavily booby-trapped with improvised explosive devices (IEDs), has since resumed service provision and, more recently, converted into a center focused solely on COVID-19 cases. According to the hospital manager, Dr. Mohammad Nadhim Ismael, Al Shifaa has 18 doctors on staff and 38 beds, and it is planning to add an additional isolated 40 beds in the coming months. Over the last month and half, Dr. Ismael reported that the hospital received around ten to thirty suspected cases a day, although that figure has now declined to around only six suspected cases daily. All the coronavirus tests administered at Al Shifaa are sent to a WHO-managed lab in Baghdad. The hospital has also received medical supplies from international organizations seeking to address and prevent shortages.

Doctors pray together in COVID-19 protective gear at the Al-Shifa Hospital in Mosul.

Photo credit: Dr. Arif Al-Azzawe & Dr. Nadhim Ismael

The Ministry of Health and WHO have asked for NGOs and international organizations already working in vulnerable communities to support COVID-19 awareness and prevention, especially those working with internally displaced people (IDPs) living in camps. Camps are incredibly susceptible to the virus, as “staying home” means confinement in 4×6 meter tents that can only house, on average, five people, including children. In general, IDPs in liberated and displaced areas have had poor medical facilities and limited practitioners. Not only does provision of testing for COVID-19 remain a hurdle, but basic protective gear is also limited, according to an interview of an NGO employee working in a camp near Dohuk. Additionally, camps that hold ISIS sympathizers and families have been notoriously underserved and could become a large concern if not properly monitored.

One camp in Chamesku, located in northern Iraq near Dohuk, has ten primary healthcare staff and seventeen volunteers who are informing, instructing, and educating the community on best health practices, COVID-19 prevention, and hand-washing. According to a volunteer with a French NGO, movements in the camp is restricted, and anyone seeking access to the camp or its health center must undergo a temperature check before entry. If a patient in the camp believes they have COVID-19, a health and hygiene practitioner interviews him/her to confirm symptoms. In the unfortunate case that Corona is confirmed, the patient is then transferred to an isolation room adjacent to the primary healthcare center. Dr. Ismael from the Al Shifaa Hospital in Mosul stated that management is in regular contact with nearby camps and supports them if a case is identified. The downside in COVID-19 awareness and working with IDPs is that it can cause mass hysteria, especially in a group that has already experienced an exceptional amount of trauma and loss. An NGO worker who asked to be anonymous reported that “people are more scared of Corona than of ISIS.” Communities within the camps have escaped life under the terror group but now feel vulnerable and powerless to escape the virus.

Social unrest and the economy

Protests in Baghdad have been ongoing since 2011 and often take place around the gates and entry points to the Green Zone. Yet, October 2019 was a turning point: the protest movement expanded to represent a larger grouping of grievances that ignored sectarian divides. Instead, the diverse demonstrators demanded jobs, an improved economy, strengthened civil society, and other public services. That month, the resignation of Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi was seen as a victory for the protestors, who had effectively channeled popular will to force a resignation for the first time since the post-2003 democratic transition began.

Despite this success, however, the outbreak of COVID-19 in late 2019 paralyzed the protests in Baghdad, forcing demonstrators to abandon the protest epicenter in Tahrir Square until the pandemic subsided. This does not imply that protestors’ resentment has disappeared; rather, they continue to hold the new prime minister-designate responsible for tackling their demands, most of which will remain unanswered until a new government forms. Moreover, the government’s use of the police, military, and popular mobilization units (PMU) to enforce curfew and keep civilians out of the streets has only exacerbated preexisting grievances, especially since these same forces brutally crushed the protestors in the last six months. It will be important to watch how Kadhimi mobilizes the police and military apparatuses, as this could inflame social unrest in the coming months if not sensitively handled. This is especially pressing, as Iranian influence within Iraq is directly tied to the PMU, and, following the physical defeat of ISIS in which they lost their caliphate, Iranian-backed blocs have increased in numbers and in their representation in the government. In November 2019, protestors burned down the Iranian consulate in Najaf in response to Iran’s meddling in Iraqi politics. More recently, Iraq has resisted being pressured by Iran to open borders and resume trade, despite being hard hit by COVID-19. Though Kadhimi has no formal affiliations to political blocs, he has been accused by the PMUs of being an American Spy. However, the PMU leaders and Iranian-backed political parties in parliament chose not to oppose his appointment as prime minister-delegate. For Kadhimi, reducing their political leverage at a later time will be an arduous task, especially since he will rely on these groups in the near-term.

Dependency on oil

The drop in oil prices since the outbreak of COVID-19 will affect Iraq’s response to the pandemic, as well as its ability to transform demands into actions, since 93% of the budget relies on oil exports. Starting on April 12th, the Iraqi government announced that it would reduce its oil production, especially as the commodity hit an all-time record low this month. This crisis could lead to measures similar to those employed in 2015, when the government froze government salaries in response to low oil prices and soaring costs in fighting the Islamic State. At that time, austerity measures were put into place, and these ultimately contributed to much of the current resentment because of poor governance and financial mismanagement. This time around, the government must take steps to ensure effective management of public finances and protect this year’s payroll. Government jobs are around 30% of the workforce, leaving the population largely dependent on oil prices for their salary. Other non-governmental sectors, including taxi drivers, construction workers, retail employees, and domestic workers, are also affected due to the curfews and closures from the coronavirus. In 2014, the Iraq government was able to get support from other governments and the IMF to support economic stability, but it is unclear if it will enjoy similar support this time around.

Outside influencers

Nonetheless, early indications point to at least a moderate level of international backing from the U.S., which, on April 7, announced its intent for a new strategic dialogue (estimated to begin in June) to review the American role in economic and security stabilization. As US-Iran tensions increase, often leaving Iraq in the crossfire, it will be important to watch how these talks alter the current US-Iraq relationship, and the Iraq-Iran axis. The US-Iraqi link is an unusual one, not found anywhere else in within the Middle East, and therefore, it is important for both sides to know exactly how they want to move forward in their relationship. Since 2003 and the US led invasion that toppled the dictator Saddam Hussein, the US has a vested interest in Iraq’s success as a state. It’s presence in Iraq is key to ensure Iraq can maintain its sovereignty and counter security threats from Iran and the Islamic State. With a recent uptick in ISIS attacks during the coronavirus lockdown, Kadhimi is also in a position to negotiate a mutually beneficial security relationship with the US that does not upset Iran.

Conclusion: A moment for good governance?

The COVID-19 outbreak and the formation of a new cabinet could be a catalyst of transformation for Iraq if grievances are properly addressed and the spread of the virus is monitored. If Kadhimi gets his cabinet approved by the start of Ramadan, this will be an opportune moment to start addressing the health sector in order to first get the virus’s spread under control. Once the government restores social stability, it can begin to address protestor’s grievances, including but not limited to economic growth. Iraq needs a prime minister who can combat corruption, improve government effectiveness, and direct resources toward infrastructure and service improvements. This will be an uphill battle as the Iraqi government has survived civil war, insurgency, and previous protest movements. The elite stakeholders who have held power within the government since 2003 will be resistant to changing the system, as it ultimately threatens their rule. Despite the magnitude of the crises Iraq faces, Kadhimi needs to negotiate new government rules to avoid returning to the normal, yet dysfunctional post-2003 political system.

If parliament confirms Kadhimi as prime minister, he will need to approach talks with the US strategically and ensure he and his government are clear in their objectives. All of Iraq’s overlapping dilemmas could combine to create the incentive to finally change the status quo: address the protesters demands, stabilize the economy, improve civil society, and address the US-Iran relationship on Iraq soil. Creating long-term change that addresses and slowly reforms the political establishment could create legitimacy and confidence in a new system that can begin – finally – to give back to the population.

About the Author

Christa Waegemann, based in Berlin, works on a USAID funded project that focuses on strengthening and improving local governance and civil society in Syria. Previously, Christa was the Program Development and Portfolio Manager at a German NGO managing programs in Jordan, Palestine and Egypt. During 2016-2017, Christa was the Country Director for an Iraqi and subsequently a French NGO in Iraq during the war against ISIS, implementing emergency aid and development projects through-out the north Kurdish region and southern central region. She has a Master’s Degree from the Hertie School of Governance in Public Policy and wrote her thesis on Iranian proxy militias/political parties in Iraq.