Iranian Kurdish Porters Face Death With Every Trip Into Iraq

By Khalid Fatah

Iranian Kurdish men have turned to smuggling in order to make a living amidst rampant unemployment along sections of the 1,450 km Iraq-Iran border. But these kolbers, as the porters are known, face grave danger with every trip they take, and often end up wounded or dead over the course of their careers.

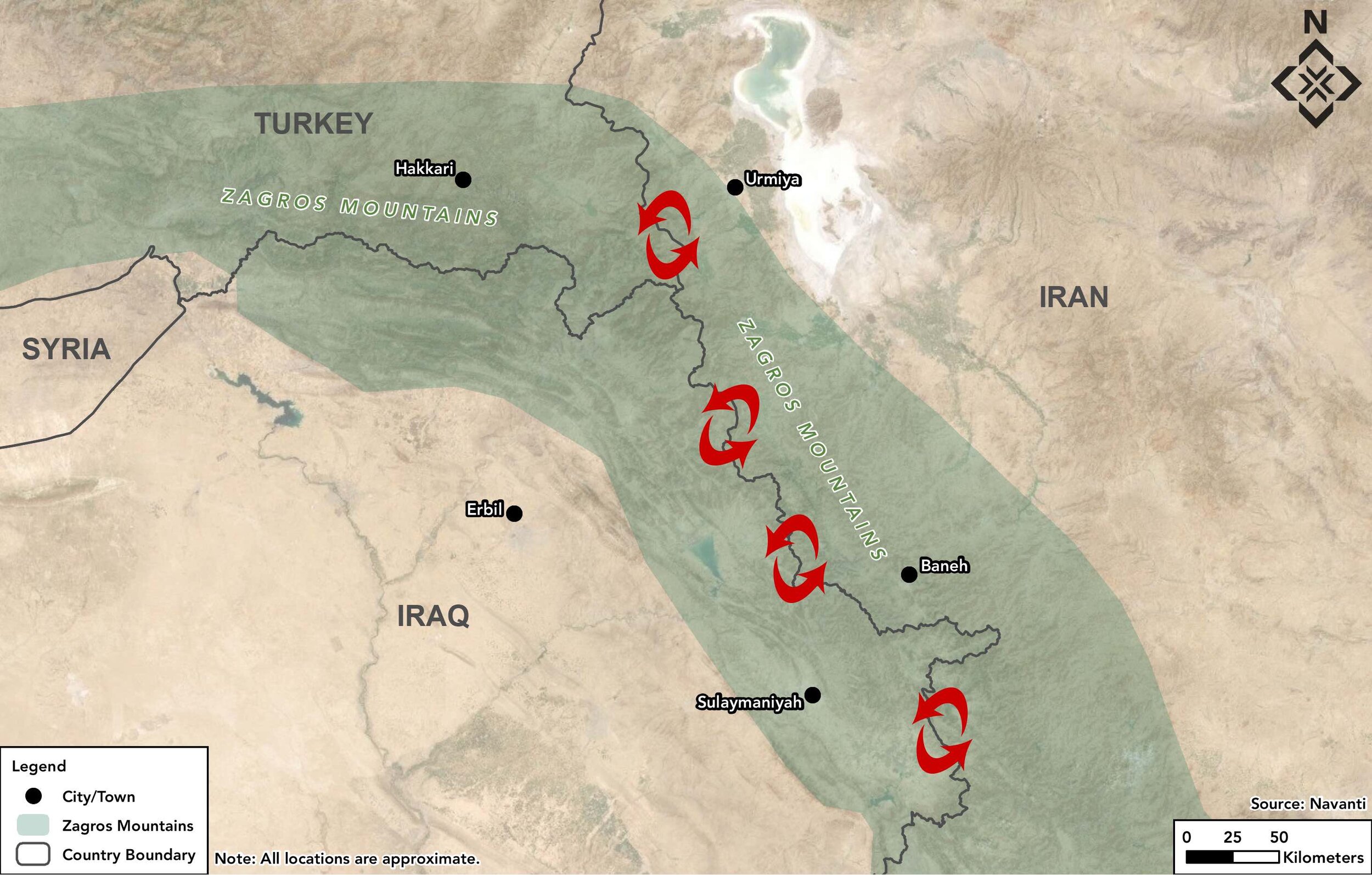

Kolbers carry an average of 75 kilograms (150 pounds) on their backs as they journey across the expansive Zagros Mountains, back and forth from the Iraqi Kurdistan region into the Iranian Kurdistan region. They mainly smuggle tobacco products, auto parts, and home appliances. In Kurdish, ‘kol’ means back and ‘ber’ means bearer—though it is a simple word, it has come to represent the adversity and tragedy facing Kurdish families in northwest Iran. These people inhabit border villages and towns in Kurdish-majority districts that have been forgotten or marginalized by Iranian authorities. Residents are left with the dangerous kolber job as their only option to make money, walking long distances in mountainous terrain through extreme weather conditions.

Stories of kolbers killed after falling from heights, or being exposed to the elements are common: in one incident in April of this year, three kolbers died from the cold in the mountains near Piranshahr. In addition, landmines planted during the Iraq-Iran war in the 1980s routinely injure kolbers, while Iranian border patrols do not hesitate to shoot live ammunition should they spot the porters.

Kolbers travel back and forth across the Zagros Mountains that run through Turkey, Iran, and Iraq. Source: Navanti

Long-term poverty draws men to this high-risk profession

The Iranian unemployment and poverty statistics, published under the name “Shakhisy Falakat” (“Misery Index”), indicate that there is no significant difference in unemployment rates in ethnic minority areas compared to Persian-majority areas. For example, 2018 data shows that unemployment in the western and southern regions of Iran (Kurdish-Arab regions) sat at an average of 13%, which was found to be the same in Yazd province, where there is a Persian majority; however, this data is incorrect, according to Iranian Kurdish journalist Shahid Alawi. The Iranian government “registers daily laborers, or those who only work one day of the week as unemployed in Persian majority areas, but those same [part-time laborers] in the minority areas are considered as employed,” thus artificially reducing the unemployment rate in Kurdish areas.

Kolbers cross a stream. Source: Kurdistan Human Rights Network

A member of parliament in the Islamic Consultative Assembly representing Mariwan and Sarvabad said in December 2017, in a meeting with the Minister of Labor, that actual unemployment in Kurdish areas is 48 percent and that the area needed investment activity to combat unemployment and poor economic prospects.

In part, the sluggish economy in Kurdish-majority areas is a reflection of countrywide issues. Since the fall of the former Shah regime and advent of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979, the country has been plagued by a series of economic crises. Most recently, US President Donald Trump instituted sanctions against Iran’s oil sector in November 2018, one month after sanctions targeting Iranian automobiles, coal, and metals. The 2019 budget that Iranian President Hassan Rouhani presented to parliament was half of the 2018 budget due in part to the impact of these sanctions.

But Kurdish majority areas in Iran also suffer from deliberate marginalization, the director of the Kurdistan Human Rights Network, based in Paris, told Navanti. “If we look at this issue from the Iranian regime’s point of view, they see it as a matter of national security. The Islamic Republic of Iran believes that it is important to keep the poverty [high] in that area in order to politically exclude those in lower classes,” Mr. Rebin Rahmani said.

Kolbers trudge through the snow. Source: Kurdistan Human Rights Network

Border security and shooting to kill

Those smuggling consumer goods into Iraq, such as food and cigarettes, are fined or detained for a short period of time if they are caught. However, on the Iranian side the consequences are often more severe.

Iranian law stipulates various penalties for smugglers depending on the value of smuggled goods. For cargo up to 10,000,000 IRR ($238), the smuggler is jailed from 90 days to 6 months and fined up to 3 times the value of the goods. The highest penalty, reserved for loads worth more than 1,000,000,000 IRR ($23,750), includes up to 5 years in prison and a fine up to 10 times the goods’ value.

This is how the law works on paper. But in practice, kolbers often face one penalty—execution—regardless of their cargo.

The Kurdistan Human Rights Network has accused the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and border patrols of indiscriminately shooting at kolbers. “They killed kolbers without warning, most of the victims were killed in daytime when they [IRGC or border guards] can see clearly,” said the Human Rights Network’s Rebin Rahmani. “The routes taken by smugglers are known to the border patrols and people. Moreover, they [kolbers] have been killed at a short distance. They have been killed near the southern city of Ahwaz and northwest of Mariwan city, which is about 15 kilometers from the Iraqi border…no investigation or prosecutions of any Iranian security element are being carried out,” said Rahmani.

Kolber with donkeys. Source: Kurdistan Human Rights Network

Since the deployment of the IRGC in Kurdish areas several years ago as a security measure against the ongoing Kurdish insurgency, the killing of kolbers has increased. The Hengaw Organization for Human Rights, which records violations committed against Kurds in Iran, told Navanti that from the beginning of 2019 until August, the IRGC killed 51 kolbers, including 4 people under the age of 17. In the same period, Iranian authorities injured 119 kolbers, 98 of whom were shot.

The Iranian government claims that it targets porters that assist Kurdish opposition militias, such as the leftist-nationalist PJAK group, or the communist Komala party. But the Kurdistan Human Rights Network’s Rahmani denies that kolbers carry cargo that could be useful to insurgent groups. He states, “for years our organization has been monitoring the situation on both sides of the border and the kolbers’ movements. During this period of the time, we did not see any documents from the Iranian authorities confirming that there was smuggling of weapons or drugs in that area.”

Paying for the landmine that severed his leg

L.W. is a kolber who spoke under the condition of anonymity to Navanti. He lost an eye and a leg on one of his journeys after a landmine exploded under his feet. He had been working as a kolber for 24 years, after he stopped going to school in sixth grade in order to help support his family. Now he is in his thirties, married with two children, and lives in Shinay village northwest of the city of Piranshahr.

Why did L.W. decide to work as a kolber for 24 years? “I must provide food for my family. There are no other jobs in our region,” he said. “I did not smuggle any forbidden goods such as alcohol, I used to bring cigarettes and appliances…for the past two years I have been handicapped [because of the landmine accident]. I spent everything I saved during the years [of work] for treatment on my injuries.”

Iranian authorities’ actions against kolbers do not stop at the border. Iran forbids the use of government health programs to treat anyone who is injured in an “unlawful” act, and in fact fines kolbers for damaging government property when they detonate landmines.

“I am not able to provide 4 million Rials ($95) for rent. A few days ago, I received a warning from the court, fining me 11 millions Rials ($261 USD) for the damage caused by the detonation of the government’s landmine that cut off my leg.”

L.W. after he was injured by a landmine. Source: L.W.

Despite the great tragedies the residents of this isolated region are facing, international media organizations have largely been silent on the lives of the kolbers. There was no mention of the kolber phenomenon before the Kurdish director Bahmin Qubadi’s film “A Time for Drunken Horses,” which was screened during the 2000 Cannes Film Festival. In the movie, Kolbers gave alcohol to their horses in order to withstand the harsh weather and terrain.