Explaining Recent Tensions between Azerbaijan and Armenia Around the Lachin Corridor By Phillip Yonge

On December 12th, groups of self-proclaimed environmental activists from Azerbaijan commenced a blockade of the so-called Lachin Corridor, the only road connecting de-jure Armenia and ethnic Armenian populations in Azerbaijani-occupied Shusha (Shushi), Stepankert (Khakhendi), and surrounding villages. The road is particularly important for regional connectivity given the lack of international flights into and out of local airports, making the Lachin Corridor quite literally the only lifeline to the outside world and the resources that come with it. The environmentally motivated protest is supposedly in response to illegal mining in ethnic Armenian villages, however the group leading the demonstrations has reported links to the Azerbaijani government and represents the latest in months of building pressure from Baku on Armenian access to occupied Nagorno-Karabakh.

The demonstrators also demanded to meet with the leader of the Russian peacekeeping force in the region, Andrei Volkov, during which Volkov reportedly pledged to monitor illegal mining in the area. The Lachin Corridor has been guarded by Russian peacekeepers since the ceasefire agreement that ended the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, however Russian military obligations in Ukraine and creeping Azerbaijani gains in influence in the region have eroded the effectiveness of peacekeeping forces. As of December 14th, Russian peacekeepers have been unable to reopen the Lachin Corridor for large-scale movement of traffic; despite the contingent’s obligation to maintain stability in the region, the peacekeepers are unable to use force to administer their mandate.

South Caucasus experts worry that the Lachin Corridor demonstrations will grow to become a serious humanitarian threat to the area, especially for ethnic Armenian residents. Residents in Stepankert, Shusha, and villages along the Corridor have already reported shortages in bread and other basic food items due to the blockade while leaders of the de-facto Artsakh (Armenian name for Karabakh) government indicate that gas supplies via Azerbaijan have been cutoff. The lack of energy supplies in the region has shuttered schools and temporarily halted surgeries and other important medical functions in local hospitals and represents another step in the near-total blockade of Armenian enclaves in the region.

South Caucasus experts worry that the Lachin Corridor demonstrations will grow to become a serious humanitarian threat to the area, especially for ethnic Armenian residents. Residents in Stepankert, Shusha, and villages along the Corridor have already reported shortages in bread and other basic food items due to the blockade while leaders of the de-facto Artsakh (Armenian name for Karabakh) government indicate that gas supplies via Azerbaijan have been cutoff. The lack of energy supplies in the region has shuttered schools and temporarily halted surgeries and other important medical functions in local hospitals and represents another step in the near-total blockade of Armenian enclaves in the region.

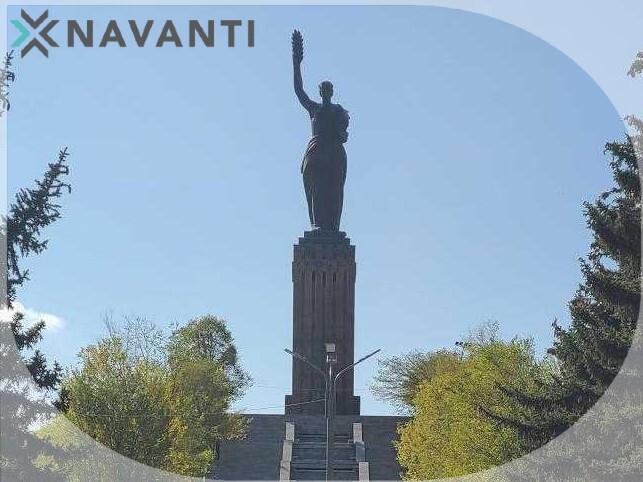

Additionally, broader concerns over the security and political ramifications of the protests threaten to thrust Azerbaijan and Armenia towards armed conflict. Some Armenian commentators have likened the Lachin Corridor demonstrators to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “Little Green Men,” who were famously at the heart of Russia’s 2014 takeover of Crimea. While Azerbaijan is well within its rights under the 2020 ceasefire agreement to protest illegal Armenian mining in the region, the dubious timing of the protests suggests more sinister motivations. Baku has gradually stepped up influence operations in Karabakh, from deliberate misinformation campaigns about Armenian “saboteurs” to infrastructure projects and political rallies in Shusha (Shushi).

Whether the demonstrations blocking the Lachin Corridor were actually motivated by illegal mining or part of larger Azerbaijani plans to gain greater control over the disputed Karabakh region, this week’s events have demonstrated the simmering conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan remains as divisive and volatile as ever. Baku and Yerevan pledged to refrain from armed conflict at a Putin-led summit in Sochi, Russia on October 31st, lending credence to the idea that protracted influence campaigns such as those demonstrated by Azerbaijan could be the future of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. However, in the immediate future, the re-opening of the Lachin Corridor should be an immediate priority for Russia, the West, and both nations involved, as a severe humanitarian crisis threatens a region that has been victim of near constant depredations since the 1990’s.

Author: Phillip Yonge is a Europe Researcher at Navanti Group. He holds an MSc from King’s College London in Eurasian Political Economics with a focus on Chinese economic initiatives in Central Asia. He studied and worked in Russia and Georgia.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s). They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Navanti Group or its partners.