In Syria’s al-Waer, Residents Adjust to a Years-Long Process of Surrender

This is the first in a two-part series examining iterative negotiations in al-Waer, the final remaining opposition-held neighborhood in Homs, Syria. Navanti Researchers on the ground in al-Waer conducted interviews and reporting in the area, gauging local views toward the ongoing negotiations. The first piece in this series provides an overview of how negotiations in al-Waer have evolved over time. The second piece will explore the how the regime implemented a strategy of “kneel and starve” in al-Waer and its toll on the civilian population.

Several times a week, Mohammed, 19, crosses a frontline between his home neighborhood of al-Waer and into the rest of Homs City, so that he can attend his university studies in English at Ba’ath University. As he approaches the edges of his neighborhood, he steels himself against unknown snipers perched in buildings, out of his sight. “At any minute you could be exposed to gunfire,” he says. “Snipers do not differentiate between [armed men] and civilians or students. I am like a prisoner on my own two feet.”

A resident of al-Waer, the last rebel-held neighborhood in the central city of Homs, Syria’s third largest, Mohammed is one of several residents who, years ago, reached a decision he had sworn he never would. Exhausted, hopeless, and hungry after years of conflict with the Syrian government and local militias, the residents of al-Waer decided in 2014 to begin a careful process of negotiating with the government for their own surrender.

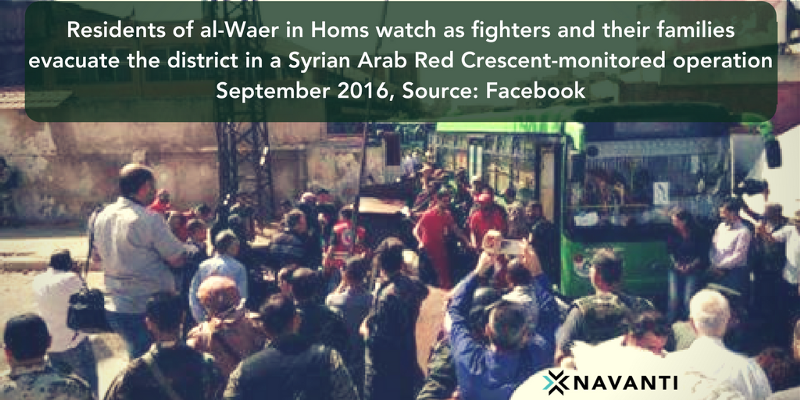

Residents formed a Negotiating Committee charged with coming to an agreement with the regime to end the violence in al-Waer. Since its formation, the Negotiating Committee has reached two distinct, wide-ranging agreements with its interlocutors across the frontlines. First, in December 2015, the two-sides reached agreement on a multi-stage truce, replete with trust-building measures meant to create momentum for a wider settlement. In addition to an immediate ceasefire, the Syrian government partially lifted the siege on the district, allowing in some humanitarian aid and permitting some residents, including Mohammed, to attend university, pursue employment, or visit family members. The deal also stipulated that the first of a batch of armed rebels from al-Waer who rejected negotiations head to rebel-held territory in northern Homs, Idlib Province.

But six months later, the truce had stalled. The “first stage” of the agreement, scheduled to last twenty-five days, dragged on for five months. In May 2016, the government opted for military escalation. The next time the two sides reached an agreement, in August, terms for the opposition were far less favorable. In the eight-month period between the two agreements, residents had endured low-level violence and on-again, off-again siege conditions. Additionally, rebels had lost momentum in northern Homs and across Syria, dimming hopes for a rebel rescue of al-Waer.

As interminable negotiations trudge forward, it seems that getting to the negotiating table was the easy part. Amid the back and forth that began in 2014, al-Waer’s residents have had to adjust themselves to a fragile yet devastating status quo, living somewhere between war and peace. And as time went on, al-Waer negotiators faced increasingly less leverage going in to the talks. For example, reduced leverage going into the August 2016 deal was reflected in the terms of the new agreement: all rebels were now required either to leave or surrender their weapons and become regular citizens under the Syrian state. Another 300 militants soon left al-Waer. In exchange, the government released two hundred prisoners, and again partially lifted the siege on al-Waer siege. But over two years after negotiations began, the violence has not stopped; in November, another bout of shelling killed dozens of civilians in the district.

For Mohammed, the wait for a lasting agreement has been interminable. On days he attends his classes, as he leaves his battered and impoverished neighborhood, where government bombings killed more than fifteen in the last month alone, he is immediately struck by the differences in broader Homs City, where he observes what he calls “the quiet life, where people just go about their jobs.”

>

“As negotiations continue, he says, “I ask myself, will we live in al-Waer how the rest of the city lives? Or will we stay like this all of our lives, only seeing quiet and safety in other places without feeling it ourselves?””

Despite the challenging process of bringing an end to the violence, residents still see the Negotiating Committee as a legitimate representative of their neighborhood and want to see negotiations continue.

>

““There’s no other choice,” said a photographer in al-Waer, contacted by WhatsApp. “We just want to live.””