Bread and Tea: A Look Into Yemen’s Food Security Crisis by Amber Liskey

Navanti has been continually engaged in data collection on the ground throughout Yemen since 2015, offering firsthand knowledge and in-depth analysis of multidimensional impacts of conflict on human security. Navanti Food Security Analyst Amber Liskey interviewed women heading households in Ta’izz, one of the epicenters of conflict, to learn more about their experiences of preparing meals for their families amid ongoing food insecurity.

Since 2015, Yemen has been embroiled in ongoing civil war between the Internationally Recognized Government (IRG) and the northern forces (Ansar Allah). Critical infrastructure such as roads, healthcare centers, schools, marketplaces and services have been targets of attack, making it hard for civilians to access basic daily resources such as food and clean drinking water. The COVID-19 pandemic has put an even bigger strain on Yemen’s already exhausted resources. In 2020, only 51% of Yemen’s health facilities were functioning. Now, over two years since the IRG and Ansar Allah [Houthis] signed the UN-brokered Stockholm Agreement, fighting between these two groups continues with no end in sight.

Yemen has become nearly synonymous with food insecurity

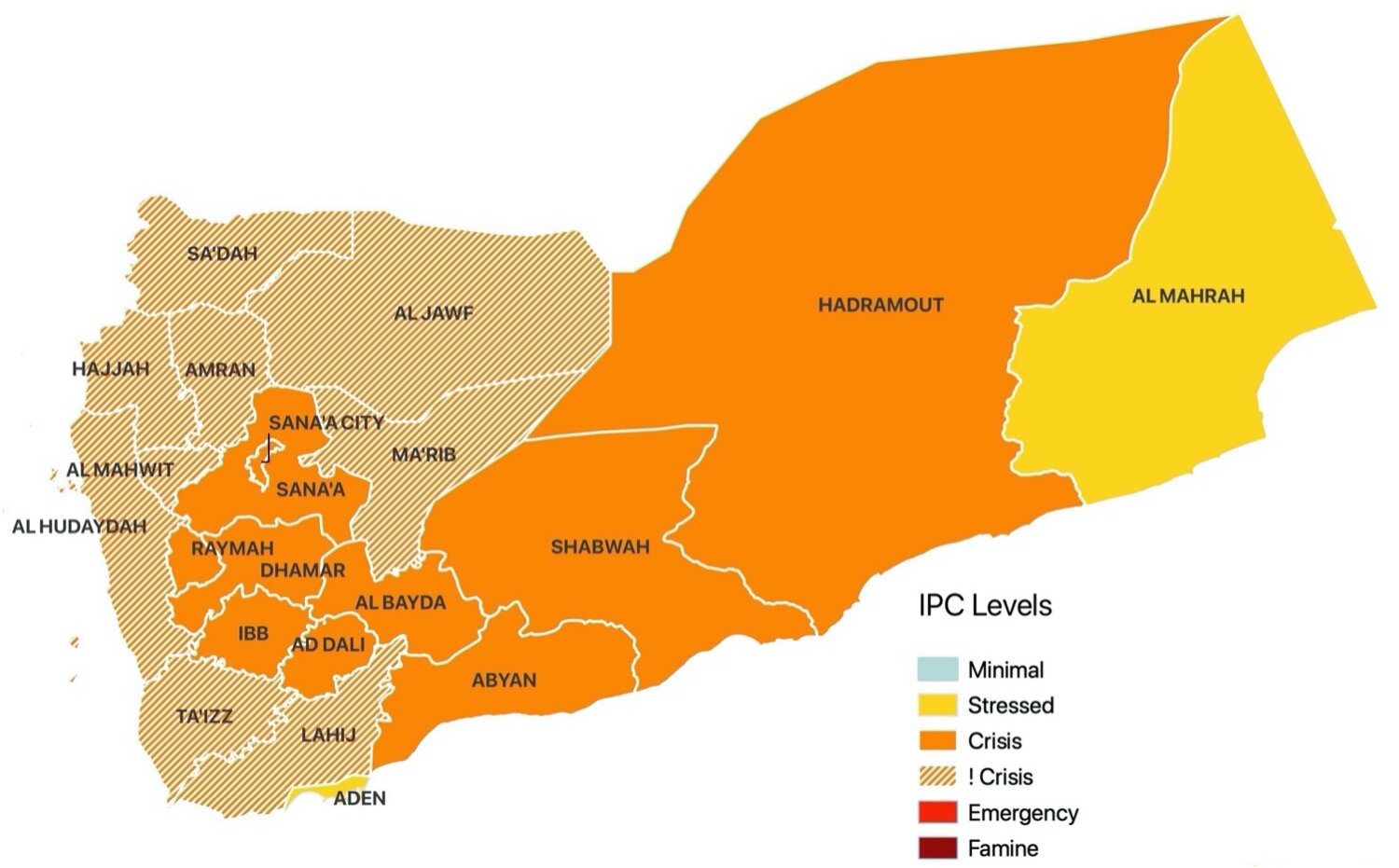

Continued depreciation of the Yemeni riyal has resulted in exponential price increases. Food prices doubled between 2015 and 2020, and continue to rise, while the number of employed Yemenis decreased by half over the same period. As food security continues to deteriorate, around two-thirds of the Yemeni population are now in need of food and livelihood support. According to the December 2020 FEWS NET Food Security Outlook Update, much of the country is classified as crisis level food insecure (IPC Phase 3); without the presence of humanitarian aid many of these areas would slip into an emergency-level food insecurity situation.

Map 1. Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) levels as of December 2020, Source: adapted from FEWSNET

! Crisis: Would likely be at least one phase worse without current or programmed humanitarian assistance

Alarming levels of food insecurity in Ta’izz

Split between the IRG, Ansar Allah, and Joint Resistance Forces (JRF) control, Ta’izz governorate and its capital Ta’izz City have been at the center of some of the most intense fighting in the country. Residents are often victim to indiscriminate violence, stray shells, and forced displacement. Access to the city and surrounding areas have been a major ongoing challenge for humanitarian aid organizations, hindering their ability to deliver aid to those who need it most. Direct routes and humanitarian corridors into the city continue to be closed, and civilians must travel by long detours just to access basic services. In a recent IPC assessment, Ta’izz was found to have the largest number of people in crisis or emergency food insecurity, at nearly 600,000.

Map 2. Map of Ta’izz governorate and location of household interviews, Source: Navanti

But what does the lived experience of hunger look like on a day-to-day basis? Navanti spoke with several female head of households in Ta’izz City and nearby rural areas (Map 2) to help bring the issue of food insecurity in Yemen into full focus. The women agreed to be interviewed and share details of their daily lives and how they struggle to feed their families in the midst of the conflict.

Food access struggle leads to adults skipping meals

A household of limited means in Ta’izz might eat a breakfast of tea with sugar, often seasoned with fragrant cardamom and cinnamon, sometimes with milk, and a home-baked flatbread (fatteh). For lunch, a sauce of potatoes might be served alongside rice; for dinner another round of flatbread dipped in a tomato-based hot pepper sauce (sahawek) and a simple yogurt sauce on the side. Once or twice a week, a porridge (asida) made of wheat flour, water, and salt might be eaten. (See Appendix A: For recipes). On special occasions, a household may prepare chicken. But for a growing number of households, meeting even the minimum amount of food required is difficult.

A family in Ta’izz shares a meal, Source: Navanti

All of the women Navanti spoke with told us they had difficulty providing three daily meals for all members of their household; family members often had to eat whatever leftovers there were from lunch for dinner or skip meals altogether. On days when food was scarce, the adults in the family ration the food so the children can eat as they are less able to tolerate hunger.

“We keep some food from lunch to dinner then we feed the children first and if there is something left, we eat…”

“Oftentimes we do not eat breakfast or dinner, we make do with one meal only … There are many days our eldest son does not eat dinner and the eldest daughter eats just enough to satisfy her hunger, and sometimes they do not eat anything in order for their younger siblings to eat.”

“At least three times a month we don’t eat for an entire day because we cannot afford to buy flour, rice, or oil. Sometimes we can borrow food from neighbors or buy food on credit from the market, but other times this is not an option…”

Typical meal of flatbread and sahawek (hot pepper sauce) and yogurt, Source: Navanti

In the early days of the conflict, households could borrow money from relatives and neighbors or buying on credit had been used as a safety net strategy when food became scarce. At this time, more people had access to regular salaries and daily work, and food prices were relatively low. As the conflict has progressed, these options have dwindled as many Yemenis are unable to spare extra food to share and shopkeepers can no longer risk selling on credit without collateral or a guarantee of payment.

“Before the war, it was better than now…there were jobs, everything was available at reasonable prices, and I could buy food, whether in cash or on credit.”

“One day we did not have money for flour, and we sat hungry at noon. After that, I went to the grocery store owner and gave him my right gold earring as collateral for him to give us half a bag of flour. I took the flour and went home to show the girls – they were so happy. They made porridge for us, and we had lunch by 2 pm. While I watched them fixing the food, tears fell on my cheek.”

The most reliable period of access to food is during Ramadan, when charitable giving typically increases. However, access to food drops off again after the holiday season and in the winter months after the end of the rainy season, which typically runs from mid-April to August, when the fall’s harvest is exhausted.

Expenses vastly exceed income

While the women in each household manage domestic life, their husbands, fathers, and eldest sons search for daily work opportunities. In most of the households interviewed, the men most commonly worked as motorcycle taxi drivers. While there is usually a steady demand for “moto taxis”, the motorcycles reportedly break down on a regular basis and it may take time to afford necessary repairs. One mother shed a tear while as she recalled a story of her son in a recent motorcycle accident that left him injured and temporarily unable to work.

“The motorcycle is currently parked due to malfunctions and recently the motor had an accident, and my son broke his hand … there is no one to support us right now…”

Other common occupations include day laborers in construction and guarding private properties. In one of the households with which Navanti spoke, the eldest male is 70 years old and unable to work, so the female head of household earns an income by renting out a section of the house. She also raises chickens and livestock at home and sells the eggs and livestock products.

Some of the children in the households interviewed go to school. However, the costs of going to school, such as buying supplies and paying the tuition fees, are a barrier for most. Those who go to school often attend up to the sixth grade. In order to support their families, males often drop out to look for work, while females may help with household chores or work for their neighbors in exchange for small amounts of money.

Life has become more expensive over time. Since the conflict began, labor wages in Ta’izz have increased slowly compared to the rate of inflation (Figure 1). On average across the governorate, wage rates have increased only 50-60% since 2016 while the inflation rate increased 127%, meaning the cost of living has increased at a greater rate than the value of wages. In addition to inflation, primary income earners can often go days or even weeks between work.

Figure 1. Source: adapted from World Food Program (WFP) data

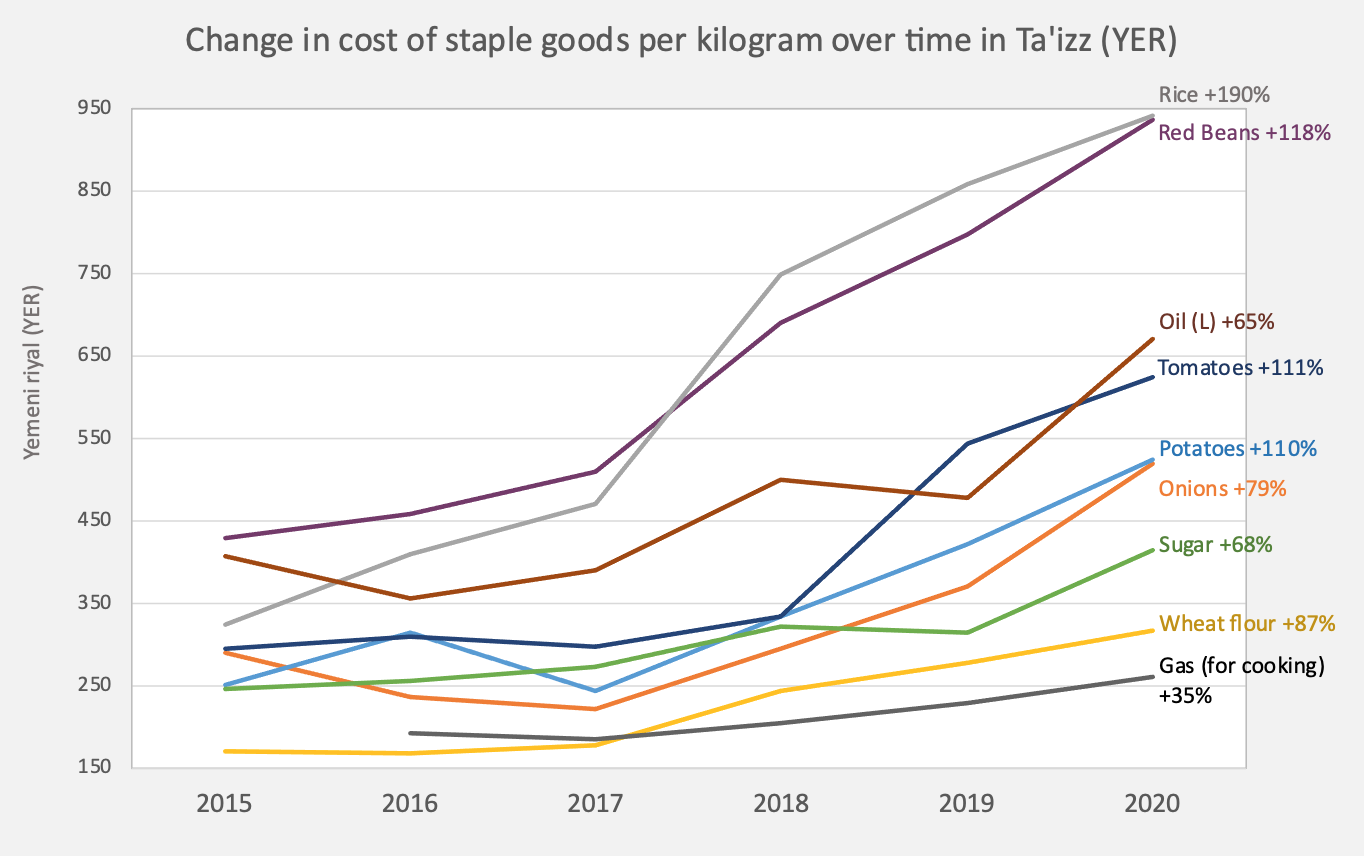

Food costs skyrocket since 2015

Food prices have increased in conjunction with the increasing inflation rate, making it increasingly difficult for households to afford basic food items. Most items have nearly doubled in price since 2015 while the cost of rice has nearly tripled (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Source: adapted from World Food Program (WFP) data

The average household size of those Navanti interviewed was seven members, averaging four members over the age of 18 and three members under the age of 18. Based on information provided by each household, we estimated the average cost of food per person per day for these households to be around 223 Yemeni riyal (YER) or just $0.25 USD per day using the parallel exchange rate of 885 YER/USD [Note: This rate of 885 YER/USD reflects the parallel market exchange rate of the Yemeni riyal new edition as of December 2020. The parallel market exchange rate of Yemeni riyal (new edition) is subject to continuous and sometimes extreme fluctuations in value], accounting for all food and non-food ingredients such as gas for cooking (Figure 3). At this cost, a seven-member household costs around 1,500 YER per day and approximately 11,000 YER per week. In a scenario where the primary income owner works only 3 days out of the week and earns approximately 15,000 YER total (based on the WFP daily average wages in Figure 1), a household would be barely able to afford this minimum level of food. For households with more members or no primary source of income, the situation could quickly become dire.

Figure 3. Average meal expenditure per person per day (YER), Source: Navanti

Note: Total average meal expenditure per day per person is 223 YER. Wheat, rice, beans, oil, sugar, and salt were categorized according to Minimum Food Basket (MFB) definition, while all other items were categorized separately.

Figure 4. Portion of diet by food type (% by weight in grams), Source: Navanti

Grains account for the majority (64%) of the average total amount of food consumed each day per person by weight in grams. Notably, vegetables make up nearly a third of the total cost, but only around 10% of the total food eaten.

It should be noted that Figure 4 is a composite of all of the households’ typical meals, and some categories such as beans and dairy are likely not available to each household on a daily basis. The combined average amount of grams per person per day was about 400 grams across households with dairy included, or 375 grams without dairy. However, some individual households fell below this threshold at closer to 300 grams per person per day.

The households we spoke with in Ta’izz were not meeting the minimum food requirements at the time of interview, according to the established minimum threshold of 1,676 calories per person per day. The caloric intake per person per day was estimated based on the average weight in grams consumed for each food category, and the Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC) Minimum Food Basket (MFB) was used as a basis for comparison (Tables 1 & 2).

Table 1. Navanti assessed average grams per day per person based on household composite

Table 2. Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC) Minimum Food Basket (MFB)

Aside from sugar, grains and oil contain the most calories per gram. To boost overall caloric intake to meet the minimum threshold at the lowest cost per calorie, households would need to increase the amount of grains and oils consumed by around 344 calories.

Displacement increases vulnerability to food insecurity

Since the beginning of the conflict, nearly four million citizens have been forced to flee their homes, with over 166,000 of the four million fleeing in 2020 alone, while many households have been repeatedly displaced as frontlines shift. In 2020, a significant number of conflict-related displacements occurred due to fighting in Ma’rib, Al Hudaydah, and Ta’izz governorates.

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) are at especially high risk of hunger and food insecurity due to the loss of their livelihoods and social safety networks. IDPs often permanently lose their homes valuables and are forced to live in IDP camps or abandoned structures. Almost all of the households with which we spoke said they have previously been displaced or are currently displaced as a result of the conflict, and most have been displaced several times.

“The conflict displaced us from our villages and houses and demolished my house in the village in Qaddaif. I have been displaced five times and we are tired of life and displacement… we don’t know where to go and during the displacement we are not getting any food and we are eating only one meal a day…”

“We were displaced from the village of Tabsha when our house was demolished by a stray shell and we came out with only our clothes…“

The families interviewed are vulnerable to bombing and shelling and remain at risk of further displacement, often separated from the clashes by only a few meters.

Home of displaced household outside of Ta’izz City, Yemen, Source: Navanti

Families face a grim future

Before the conflict began in 2015, the women interviewed told us their lives were significantly more stable—food prices were affordable, and jobs were more available. Families lived in their own homes without daily fear of being displaced. Other families earned income off their land, growing food and raising livestock. A recently conducted CARE survey found that 93% of respondents interviewed in several districts of the governorate had significantly worsened livelihoods and well-being compared to before the conflict.

“We were settled in our village, we had land to grow crops, our house belonged to us, we had livestock and chickens. Prices were very cheap. As the war continued, prices went up with everything, destroyed our house and displaced us. Everything in the house was destroyed by a shell, and the cows, sheep and chickens died.”

When asked about their expectations of the future, the women interviewed expressed concern. As the war continues, the coping mechanisms that people use to secure their needs are becoming increasingly exhausted. Insecurity and high inflation rates are affecting more and more portions of the population.

“We expect the worst as a result of weak job opportunities and the increase in food prices, the price of a bag of flour has reached twenty thousand riyals…”

Until peace agreements can be reliably implemented, many see humanitarian aid as their only hope for filling nutritional gaps and feeding their families in the foreseeable future. Still, humanitarian aid organizations have difficulty extending their reach to all populations in need. For one, Ta’izz is the most densely populated governorate. Secondly, active fighting prevents aid distributions in many areas due to employee safety concerns. None of the households interviewed currently receive any regular food assistance for this reason, but all shared the same sentiment:

“The number of households targeted by humanitarian aid distributions needs to be increased, paying special attention to the most vulnerable in areas very close to the areas of armed clashes.”

Without this life-saving humanitarian aid as a last resort, the worst-affected families face malnutrition, and even death.

Appendix A: Recipes

The following recipes were shared by the women of the households Navanti spoke with. The recipes are traditional everyday Yemeni dishes.

Fatteh (consisting of grain and milk)

Ingredients:

A quarter of a kilo of flour

Two teaspoons of oil

Liter of water

Quarter teaspoon of salt

Half a liter of liquid milk

Cooking instructions:

1) Pour the flour into a clean container, then pour the water into it a little at a time while adding salt

2) Knead the flour with water until it becomes soft

3) Roll the dough in a circle and in the meantime, put the oil on the table

4) After the dough forms a circle, it is placed on the table with oil and stirred

5) When the dough is done it is cut into very small pieces

6) Heat the liquid milk until it is hot

7) Small pieces of bread are placed in a bowl, then milk is poured over it and mixed together

Sahawek (salsa)

Ingredients:

2 tomatoes

4 pods of basbas (hot pepper)

A quarter of a very small tablespoon of salt

Cooking instructions:

1) Wash the tomato and basbas (hot pepper)

2) The tomatoes are placed on the mill and crushed by a special stone

3) Then the basbas is crushed in the same way, on top of the crushed tomato

4) Put the tomatoes and basbas into a small bowl

5) Salt is added

Asida (porridge)

Ingredients:

Half a kilo of flour

A liter and a half of water

A small spoon of salt

Cooking instructions:

1) Water is poured into a bowl and heated

2) Pour the flour in small quantities and stir until it becomes almost solid, and at the same time add a little salt

Hulba (fenugreek)

Ingredients:

6 tablespoons of fenugreek

150 ml water

Half a teaspoon of salt

Cooking instructions:

1) Put the fenugreek in a bowl, then pour water on it and stir until it becomes soft

2) Salt is added

3) Serve with the porridge